| Reference: | S46302 |

| Author | William Hamilton |

| Year: | 1786 |

| Zone: | Ponza |

| Printed: | London |

| Measures: | 210 x 125 mm |

| Reference: | S46302 |

| Author | William Hamilton |

| Year: | 1786 |

| Zone: | Ponza |

| Printed: | London |

| Measures: | 210 x 125 mm |

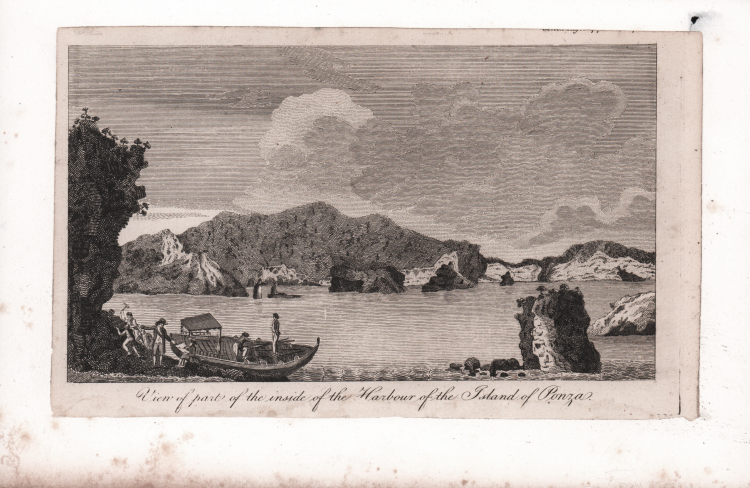

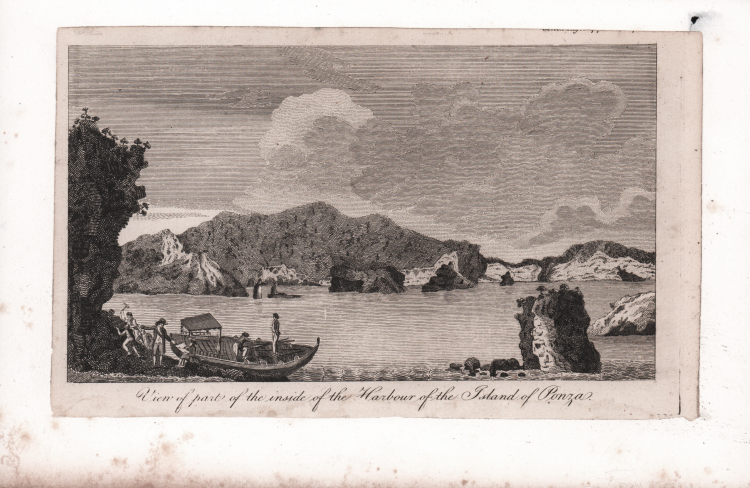

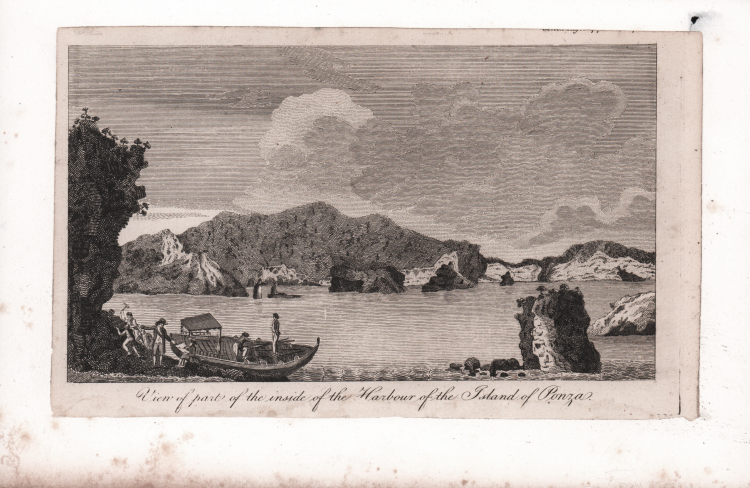

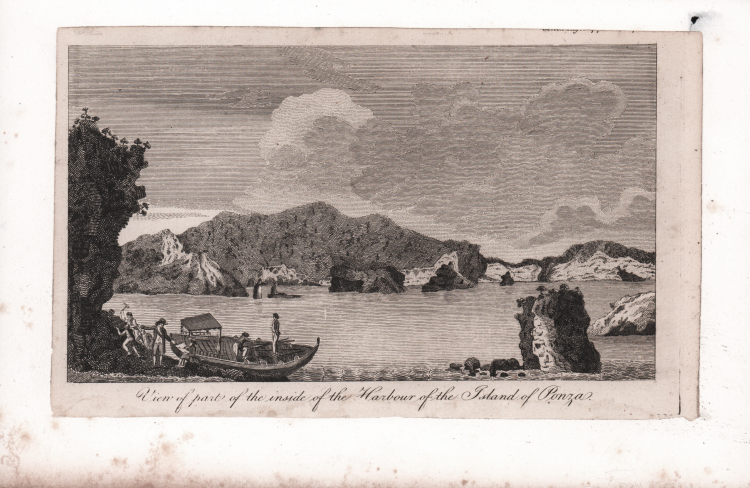

Landscape view of the harbour on the island of Ponza in the Tyrrenian Sea, Italy. The scene shows local geology caused by volcanic action, notably solidified lava flows, being viewed by the felucca party of Sir William Hamilton (1731-1803). This group includes Hamilton directing the artist and workmen with hammers taking specimens of rock (lower left).

Plate 11 from the book “Some particulars of the present state of Mount Vesuvius; with the account of a journey into the province of Abruzzo, and a voyage to the Isle of Ponza”, by Sir William Hamilton, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, vol.76 (1786), pp.365-381.

The plate is engraved after a drawing by Francesco Progenie.

Copperplate, printed on contemporary laid paper, good condition. Rare.

William Hamilton (Henley-on-Thames, 13 dicembre 1730 – Londra, 6 aprile 1803)

|

Sir William Hamilton was a Scottish diplomat, antiquarian, archaeologist and vulcanologist. After a short period as a Member of Parliament, he served as British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples from 1764 to 1800. He studied the volcanoes Vesuvius and Etna, becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society and recipient of the Copley Medal.

Hamilton arrived in Naples on 17 November 1764[8] with the official title of Envoy Extraordinary to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and would remain as ambassador to the court of Ferdinand and Maria Carolina until 1800, although from November 1798 he was based in Palermo, the court having moved there when Naples was threatened by the French Army. As ambassador, Hamilton was expected to send reports back to the Secretary of State every ten days or so, to promote Britain's commercial interests in Naples, and to keep open house for English travellers to Naples.[9] These official duties left him plenty of time to pursue his interests in art, antiquities, and music, as well as developing new interests in volcanoes and earthquakes. Catherine, who had never enjoyed good health, began to recover in the mild climate of Naples. Their main residence was the Palazzo Sessa, where they hosted official functions and where Hamilton housed his growing collection of paintings and antiquities; they also had a small villa on the seashore at Posillipo (later it would be called Villa Emma), a house at Portici, Villa Angelica, from where he could study Mount Vesuvius, and a house at Caserta near the Royal Palace.

Hamilton began collecting Greek vases and other antiquities as soon as he arrived in Naples, obtaining them from dealers or other collectors, or even opening tombs himself.[10][11] In 1766–67 he published a volume of engravings of his collection entitled Collection of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman antiquities from the cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton, His Britannick Maiesty's envoy extraordinary at the Court of Naples. The text was written by d'Hancarville with contributions by Johann Winckelmann. A further three volumes were produced in 1769–76.[12] During the his first leave in 1771 Hamilton arranged the sale of his collection to the British Museum for £8,400.[13] Josiah Wedgwood the potter drew inspiration from the reproductions in Hamilton's volumes.[12] During this first leave, in January 1772, Hamilton became a Knight of the Order of the Bath[14] and the following month was elected Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries.[15] In 1777, during his second leave to England, he became a member of the Society of Dilettanti.

When Hamilton returned to England for a third period of leave, in 1783–84, he brought with him a Roman glass vase, which had once belonged to the Barberini family and which later became known as the Portland Vase. Hamilton had bought it from a dealer and sold it to the Duchess of Portland. The cameo work on the vase again served as inspiration to Josiah Wedgwood, this time for his jasperware. The vase was eventually bought by the British Museum.[16] He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1792.[17]

In 1798, as Hamilton was about to leave Naples, he packed up his art collection and a second vase collection and sent them back to England. A small part of the second vase collection went down with HMS Colossus off the Scilly Isles. The surviving part of the second collection was catalogued for sale at auction at Christie's when at the eleventh hour Thomas Hope stepped in and purchased the collection of mostly South Italian vases.

Soon after Hamilton arrived in Naples, Mount Vesuvius began to show signs of activity and in the summer of 1766 he sent an account of an eruption, together with drawings and samples of salts and sulphurs, to the Royal Society in London. On the strength of this paper he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the autumn of 1767 there was an even greater eruption and again Hamilton sent a report to the Royal Society. The two papers were published as an article in the Society's journal Philosophical Transactions.[18][19]

The Royal Society awarded him the Copley Medal in 1770 for his paper, "An Account of a Journey to Mount Etna".[20] In 1772 he published his writings on both volcanoes in a volume called Observations on Mount Vesuvius, Mount Etna, and other volcanos. This was followed in 1776 by a collection of his letters on volcanoes, entitled Campi Phlegraei (Flaming fields, the name given by the Ancients to the area around Naples). The volume was illustrated by Pietro Fabris.

Hamilton was also interested in earthquakes. He visited Calabria and Messina after the earthquake of 1783 and wrote a paper for the Royal Society

|

William Hamilton (Henley-on-Thames, 13 dicembre 1730 – Londra, 6 aprile 1803)

|

Sir William Hamilton was a Scottish diplomat, antiquarian, archaeologist and vulcanologist. After a short period as a Member of Parliament, he served as British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples from 1764 to 1800. He studied the volcanoes Vesuvius and Etna, becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society and recipient of the Copley Medal.

Hamilton arrived in Naples on 17 November 1764[8] with the official title of Envoy Extraordinary to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and would remain as ambassador to the court of Ferdinand and Maria Carolina until 1800, although from November 1798 he was based in Palermo, the court having moved there when Naples was threatened by the French Army. As ambassador, Hamilton was expected to send reports back to the Secretary of State every ten days or so, to promote Britain's commercial interests in Naples, and to keep open house for English travellers to Naples.[9] These official duties left him plenty of time to pursue his interests in art, antiquities, and music, as well as developing new interests in volcanoes and earthquakes. Catherine, who had never enjoyed good health, began to recover in the mild climate of Naples. Their main residence was the Palazzo Sessa, where they hosted official functions and where Hamilton housed his growing collection of paintings and antiquities; they also had a small villa on the seashore at Posillipo (later it would be called Villa Emma), a house at Portici, Villa Angelica, from where he could study Mount Vesuvius, and a house at Caserta near the Royal Palace.

Hamilton began collecting Greek vases and other antiquities as soon as he arrived in Naples, obtaining them from dealers or other collectors, or even opening tombs himself.[10][11] In 1766–67 he published a volume of engravings of his collection entitled Collection of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman antiquities from the cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton, His Britannick Maiesty's envoy extraordinary at the Court of Naples. The text was written by d'Hancarville with contributions by Johann Winckelmann. A further three volumes were produced in 1769–76.[12] During the his first leave in 1771 Hamilton arranged the sale of his collection to the British Museum for £8,400.[13] Josiah Wedgwood the potter drew inspiration from the reproductions in Hamilton's volumes.[12] During this first leave, in January 1772, Hamilton became a Knight of the Order of the Bath[14] and the following month was elected Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries.[15] In 1777, during his second leave to England, he became a member of the Society of Dilettanti.

When Hamilton returned to England for a third period of leave, in 1783–84, he brought with him a Roman glass vase, which had once belonged to the Barberini family and which later became known as the Portland Vase. Hamilton had bought it from a dealer and sold it to the Duchess of Portland. The cameo work on the vase again served as inspiration to Josiah Wedgwood, this time for his jasperware. The vase was eventually bought by the British Museum.[16] He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1792.[17]

In 1798, as Hamilton was about to leave Naples, he packed up his art collection and a second vase collection and sent them back to England. A small part of the second vase collection went down with HMS Colossus off the Scilly Isles. The surviving part of the second collection was catalogued for sale at auction at Christie's when at the eleventh hour Thomas Hope stepped in and purchased the collection of mostly South Italian vases.

Soon after Hamilton arrived in Naples, Mount Vesuvius began to show signs of activity and in the summer of 1766 he sent an account of an eruption, together with drawings and samples of salts and sulphurs, to the Royal Society in London. On the strength of this paper he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the autumn of 1767 there was an even greater eruption and again Hamilton sent a report to the Royal Society. The two papers were published as an article in the Society's journal Philosophical Transactions.[18][19]

The Royal Society awarded him the Copley Medal in 1770 for his paper, "An Account of a Journey to Mount Etna".[20] In 1772 he published his writings on both volcanoes in a volume called Observations on Mount Vesuvius, Mount Etna, and other volcanos. This was followed in 1776 by a collection of his letters on volcanoes, entitled Campi Phlegraei (Flaming fields, the name given by the Ancients to the area around Naples). The volume was illustrated by Pietro Fabris.

Hamilton was also interested in earthquakes. He visited Calabria and Messina after the earthquake of 1783 and wrote a paper for the Royal Society

|