| Reference: | S17262 |

| Author | Primo Incisore |

| Year: | 1497 ca. |

| Measures: | 195 x 280 mm |

| Reference: | S17262 |

| Author | Primo Incisore |

| Year: | 1497 ca. |

| Measures: | 195 x 280 mm |

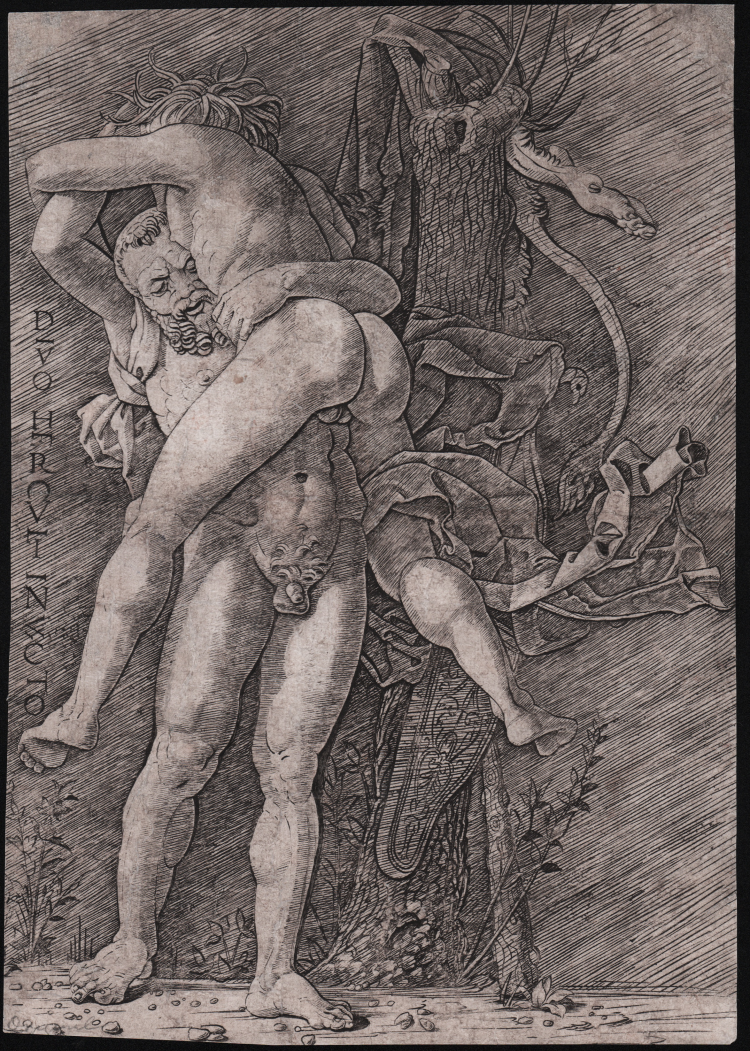

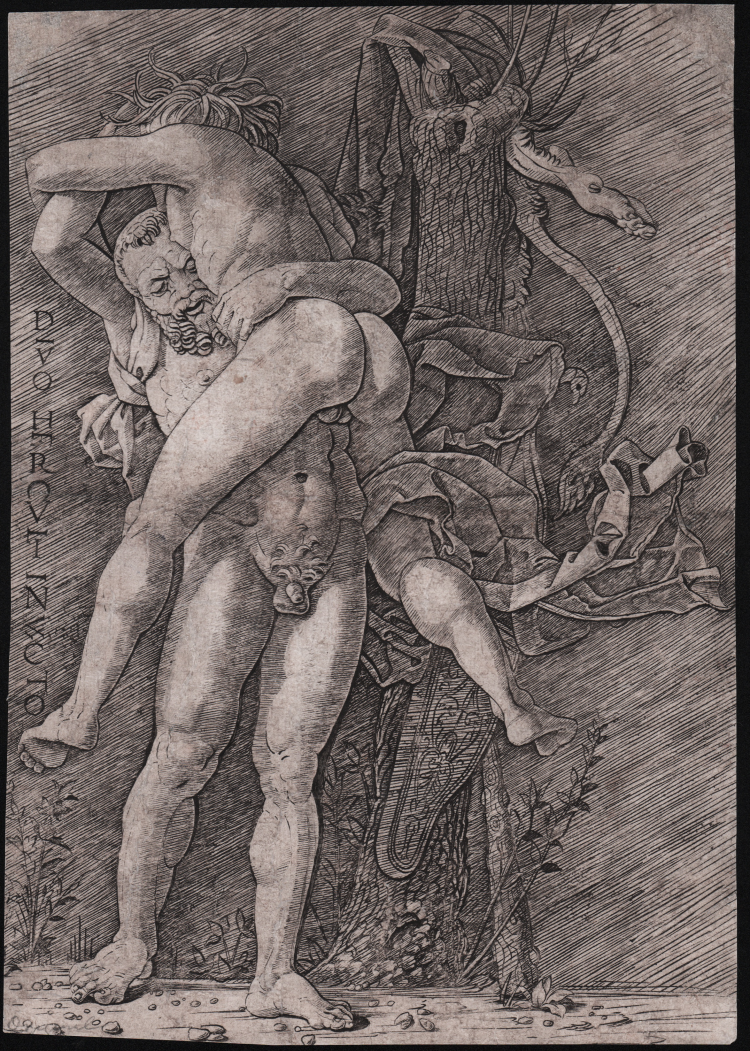

Hercules and Antaeus; Antaeus seen from behind and held by the waist; a tree trunk in the background

Engraving, 1497 circa, lettered vertically down left side: 'DIVO HERCULI INVICTO'.

The composition has been realized after the drawings of Mantegna for the Camera degli Sposi (also known as Camera Picta) room, in the Ducal Palace, Mantua; the theme of Hercules was one of the most popular during the Reinassance, particularly for Mantegna and his workshop. Apart from this work and the frescoes, there is a drawing and four engravings of the workshop, two signed by Giovanni Antonio da Brescia.

This work can be considered one of the best quality examples ever realized in the circle of Mantegna, and very close to the technique of the Maestro. In the 1992 London exhibition, Suzanne Boorsch includes the print in the corpus of engravings made by a master belonging to Mantegna's close circle, whom the scholar names "premier engraver" to emphasize his fidelity to Mantegna's engraving technique and remarkable skill. For the historical identity of this anonymous and highly gifted engraver, recent documentary findings, and already known information, seem to suggest the name of the goldsmith and engraver Gian Marco Cavalli, who was employed as an engraver by Mantegna as early as 1475 and remained in close contact with the master until his death, as evidenced by his presence at the Mantegna's testament of 1506.

“Mantegna apparently designed at least two different cycles of the deeds of Hercules. One comprises six frescoes on the ceiling of the Camera degli Sposi, while another is recorded in a document of 1463 which states that an artist named Samuele painted a room dedicated to Hercules using drawings by Mantegna.

Two basic versions of the Hercules and Antaeus scene by Mantegna are known. The composition used in the fresco of the Camera reappears in a number of variations, including several engravings and a drawing recently attributed to Mantegna. All of these versions show the figure of Hercules in a striding posture, holding Antaeus from behind or from one side, so that both the hero's arms cut into the midriff of his victim. Antaeus's legs are spread in a scissors movement. As Mezzetti (cfr. Andrea Mantegna, Catalogo della Mostra, Venezia 1961) points out, this composition is quite close to antique models, such as the sculpture group in Marbury Hall, Smith Barry Collection. The figures' great activity, their rather slender proportions, and their lack of volume are all typical of Mantegna's early works in Mantua.

The version recorded in our engraving is quite different and clearly later. Hercules' pose is more solid and more suggestive of weight, and both he and his opponent are more massive and three-dimensional figures. Because of these qualities, the group is closer to antique prototypes, both formally and spatially, than is the earlier version. In fact, Mezzetti convincingly compares our engraving with a Hellenistic statue of Hercules and Antaeus, a work which Mantegna could have seen in Rome, that displays a similar solidity and massiveness. For this reason Mezzetti dates the engraving near Mantegna's return from Rome in 1490. The dating of the composition to the post-Roman period is also supported by comparisons with the late grisaille panels, which were surely designed by Mantegna, although their execution is in dispute. The panel of David with the Head of Goliath is a particularly good comparison for the proportions of the figures, the musculature, strongly defined by shading and bright highlighting, the use of space, and even the type of hair found on Antaeus and Goliath. The Vestal Tuccia is especially close to the engraving in the type of drapery used. The manner of engraving, employing fine shading strokes within heavy outlines, is typical of the late school engravings and adds further support to a dating in the 1490s. As Hind has noted, the technique is most like Mantegna's own. The sharp demarcation between light and shadow in the modeling of the musculature is particularly close to the Battle of the Sea Gods, as is the style of the drapery.

There is a brush drawing related to our engraving in the British Museum. According to Popham and Pouncey, variations from the print indicate that the drawing is neither a copy nor a preparatory study but rather an independent work after Mantegna's original design. It could be by the draftsman of the Hercules and the Lion in Christ Church, who may be Giovanni Antonio da Brescia; on the other hand, it is no closer to Giovanni Antonio's signed engraving of Hercules and Antaeus (Hind 1) than it is to our own. In fact, the two prints do not appear to be independent; the relative carelessness of the background details in Giovanni Antonio's engraving suggest that it is a copy of ours. The idea of having Hercules and Antaeus face one another appears in other quattrocento works, most notably Pollaiuolo's statuette, which is surely independent. Mezzetti's suggestion that our engraving and another Hercules and Antaeus after Mantegna (Hind 19) represent opposite views of a sculptural prototype is reasonable, although the poses are in fact slightly different, and the engravings appear to be by different hands. In addition to its obvious significance as a mythological illustration, the theme of Hercules and Antaeus also has allegorical overtones. Hercules was regarded as an embodiment of virtue, strength, courage and compassion; Antaeus, the son of Ge, was thought to be a symbol of earthly lust, to be overcome by chastity. On an emblematic level, Mantegna's composition thus represents virtue defeating lust” (cfr. Jacquelyn L. Sheehan in Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art, pp. 218-221).

A very good impression, printed on contemporary laid paper without watermark, trimmed inside the platemark, minor repairs perfectly executed, in general in excellent condition. Like mostly works of the XV century, examples trimmed to platemark are rare to be found.

Bibliografia

Hind 1938-48 / Early Italian Engraving, a critical catalogue (17); Bartsch / Le Peintre graveur (XIII.237.16); Jay A. Levinson, Konrad Oberhuber, and Jacquelyn Sheehan, Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art, n. 83; Suzanne Boorsch, Keith Christiansen, David Ekserdjian, Charles Hope, David Landau, Andrea Mantegna (1992), p. 300.

Primo Incisore (Attivo a Mantova tra la fine del XV e l’inizio del XVI secolo)

|

Suzanne Boorsch (cfr. Andrea Mantegna (1992), p. 300) groups together the best derivations in print from Andrea Mantegna and assigns them to a master belonging to Mantegna's close circle, whom the scholar names "premier engraver" (premier engraver) to emphasize his fidelity to Mantegna's engraving technique and remarkable skill. For the historical identity of this anonymous and highly gifted engraver, recent documentary findings, and already known information, seem to suggest the name of the goldsmith and engraver Gian Marco Cavalli, who was employed as an engraver by Mantegna as early as 1475 and remained in close contact with the master until his death, as evidenced by his presence at the drafting of Mantegna's will in 1506.

|

Primo Incisore (Attivo a Mantova tra la fine del XV e l’inizio del XVI secolo)

|

Suzanne Boorsch (cfr. Andrea Mantegna (1992), p. 300) groups together the best derivations in print from Andrea Mantegna and assigns them to a master belonging to Mantegna's close circle, whom the scholar names "premier engraver" (premier engraver) to emphasize his fidelity to Mantegna's engraving technique and remarkable skill. For the historical identity of this anonymous and highly gifted engraver, recent documentary findings, and already known information, seem to suggest the name of the goldsmith and engraver Gian Marco Cavalli, who was employed as an engraver by Mantegna as early as 1475 and remained in close contact with the master until his death, as evidenced by his presence at the drafting of Mantegna's will in 1506.

|