| Reference: | S35661 |

| Author | Salvator ROSA |

| Year: | 1662 |

| Measures: | 273 x 455 mm |

| Reference: | S35661 |

| Author | Salvator ROSA |

| Year: | 1662 |

| Measures: | 273 x 455 mm |

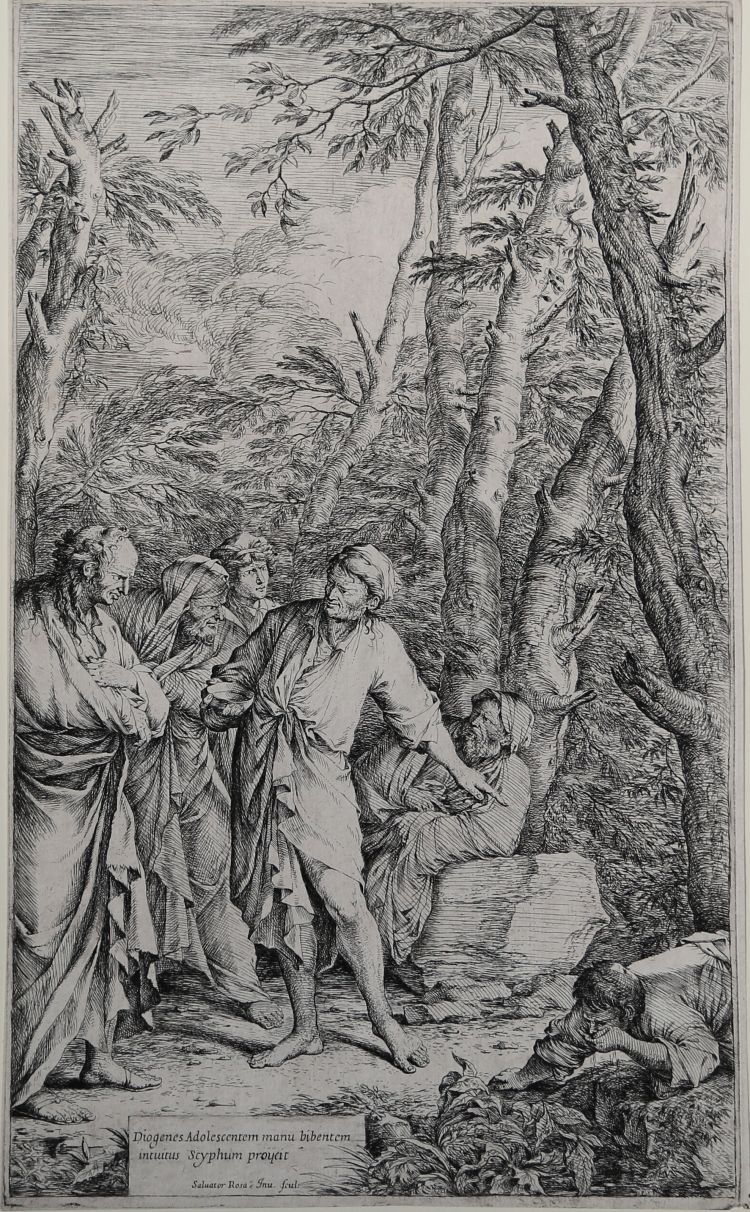

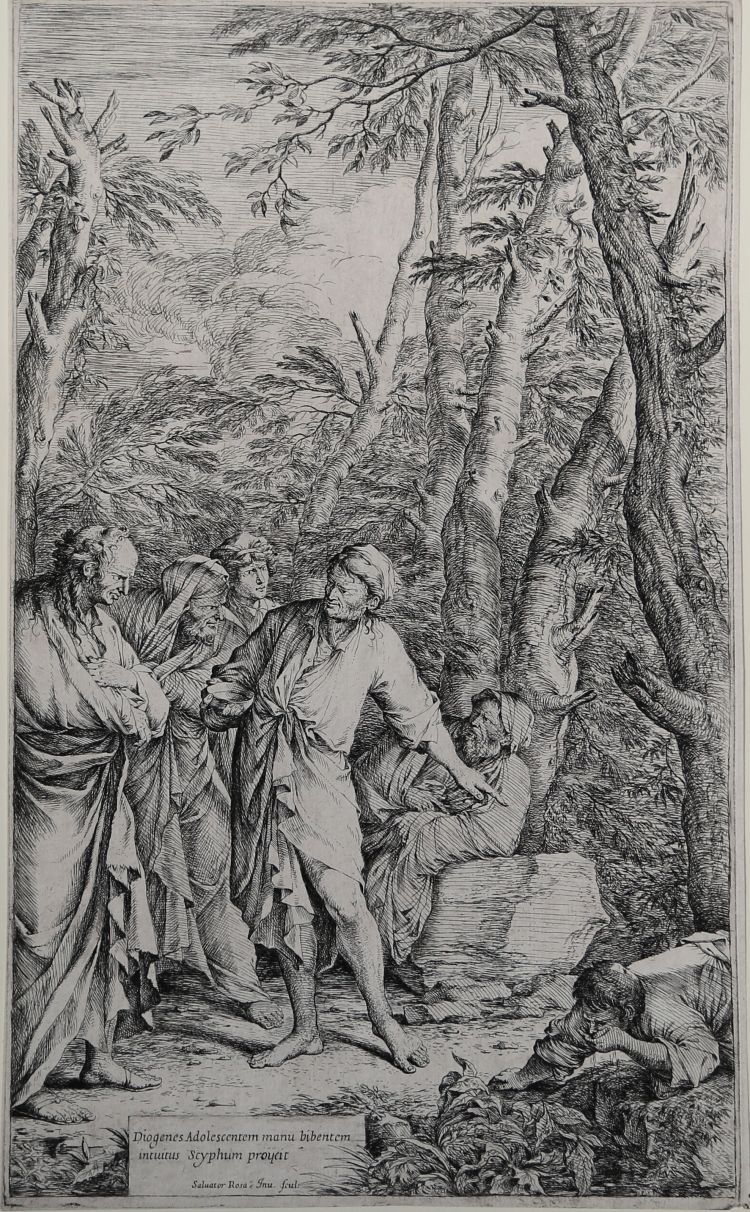

Etching, 1662, signed on plate at lower left “Salvator Rosa Inv Scul” and inscribed ““Diogenes adolescentem manu bibentem intuitus Scyphum proijcit”.

Example of first state, of two, before drypoint additions.

Magnificient early imprssion, printed on contemporary laid paper with “double encircled fleur-de-lys”, thin margins, excellent condition.

The print is, in reverse, after a Salvator Rosa painting (1651 - 52) now at SMK, National Gallery of Denmark, in Copenhagen. The painting is in pendant with Democritus in Meditation (1650–51), also in Copenhagen.

The Greek philosopher Diogenes of Sinope (c. 400–325 BCE) occupies the centre of the composition. He holds his drinking bowl in his hand as he turns to an assembly of men, showing them a boy bending down at a stream to drink out of his hands.

Being a so-called cynic (”kynikos”: Greek for “doglike”), Diogenes lived “like a dog”, i.e. with no material goods. The drinking cup was one of his few remaining possessions, and now, inspired by the boy’s example, he sees how that too is superfluous and casts it aside.

Salvator Rosa considered himself a painter-philosopher and was greatly interested in the neo-stoic ideas about ethics and moral philosophy current at the time, focusing on virtues such as endurance, constancy and restraint.

The episode shown in Salvator Rosa’s painting, and print, is one of the many anecdotes told by Laërtius about the life of Diogenes, but the story can also be found in a slightly different form in an apocryphal letter from Diogenes himself to the cynic Crates.43 All that Diogenes owned was a bag for food, a drinking cup and a spoon. When Diogenes saw a child drinking water out of its hands, he threw away his cup, saying “A child has beaten me in plainness of living”. He similarly cast away his spoon when he saw a child eating lentil gruel with a small piece of hollow bread. After these episodes he arrived at the following conclusion: “Everything belongs to the gods; and wise men [i.e. philosophers] are the friends of the gods. All things are in common among friends; therefore everything belongs to wise men”.

In 1662, long after he created the pendants, Salvator Rosa did a number of prints depicting philosophers and ascetic hermits. His paintings formed the basis for the prints depicting Democritus and Diogenes, whereas the other images – leaves showing scenes such as Diogenes and Alexander, Plato’s Academy, etc. – exist only as prints.

In the exhibition catalogue Salvator Rosa. Tra mito e magia (2008) Caterina Volpi sees Democritus and Diogenes as personifications of ‘the new man’, i.e. of the learned humanist who is as interested in studies of zoology as he is in anatomy, alchemy, astrology and Egyptology. Volpi takes the Renaissance world view expressed by the Wunderkammer distinction between artificialia and naturalia and applies it to the pendants, linking them to Salvator Rosa’s time in Florence where there was an established circle of clients for philosopher scenes among the city’s intellectual scene – unlike in Rome, where he struggled to sell the monumental pendants at the desired price. In the same exhibition catalogue Ebert-Schifferer contextualizes the Copenhagen Demokritus and Diogenes within Rosa’s memento mori and whichcraft motives in relation to the Wunderkammer of that time.

|

Bartsch, XX, n. 5; Le Blanc, n. 17; Rotili, p. 214 n. 97; TIB, 45, p. 339, n. 5; Incisori napoletani, pp. 148-149, n. 148; Salvator Rosa tra mito e magia', (2008), n. 7; Rosa – Rame…, (2014), p. 211 n. 89; Tra Mito e Allegoria, pp. 450-451 n. 172.

|

Salvator ROSA (Napoli 1615 - Roma 1673)

|

Like Testa, Castiglione and Della Bella, Salvator Rosa considered the art of engraving the best technique to express his talent and, it is not by chance that he is considered, together with the already mentioned artists, one of the protagonists of Italian seventeenth-century art.

Rosa was an extremely eclectic person; his main models in art were the classicism of Carracci, the naturalism of Ribera, the contemporary Roman painting and the ancient world.

From the latter in particular, Rosa drew inspiration for his engravings, whose subjects come from the old Stoic philosophy, with the glorification of virtues though allegories. We have also to consider his passion for esotericism, which inspired him with pictorial compositions with necromancy.

His technique and total command of etching enabled his prints to be appreciated even from his contemporaries, copied by them and highly requested by collectors.

|

|

Bartsch, XX, n. 5; Le Blanc, n. 17; Rotili, p. 214 n. 97; TIB, 45, p. 339, n. 5; Incisori napoletani, pp. 148-149, n. 148; Salvator Rosa tra mito e magia', (2008), n. 7; Rosa – Rame…, (2014), p. 211 n. 89; Tra Mito e Allegoria, pp. 450-451 n. 172.

|

Salvator ROSA (Napoli 1615 - Roma 1673)

|

Like Testa, Castiglione and Della Bella, Salvator Rosa considered the art of engraving the best technique to express his talent and, it is not by chance that he is considered, together with the already mentioned artists, one of the protagonists of Italian seventeenth-century art.

Rosa was an extremely eclectic person; his main models in art were the classicism of Carracci, the naturalism of Ribera, the contemporary Roman painting and the ancient world.

From the latter in particular, Rosa drew inspiration for his engravings, whose subjects come from the old Stoic philosophy, with the glorification of virtues though allegories. We have also to consider his passion for esotericism, which inspired him with pictorial compositions with necromancy.

His technique and total command of etching enabled his prints to be appreciated even from his contemporaries, copied by them and highly requested by collectors.

|