The Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia

Marcantonio RAIMONDI

Code:

S46885

Measures:

157 x 258 mm

Year:

1515 ca.

Christ standing facing forward, holding a cross with a banner and...

Marco DENTE detto "Marco da Ravenna"

Code:

S30424

Measures:

134 x 205 mm

Year:

1516 ca.

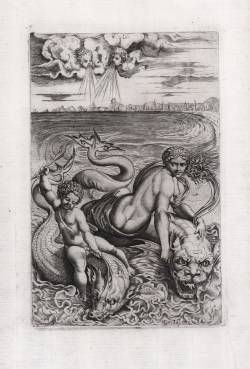

Venus on the Dolphin

Marco DENTE detto "Marco da Ravenna"

Code:

S46558

Measures:

170 x 265 mm

Year:

1516 ca.

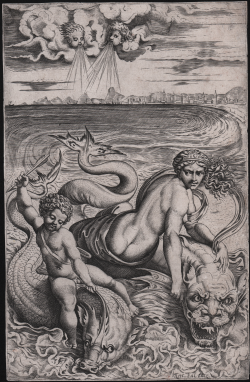

Venus and Cupid on the Dolphin

Marco DENTE detto "Marco da Ravenna"

Code:

S47035

Measures:

175 x 270 mm

Year:

1516

Triton and Nereid

Agostino de Musi detto VENEZIANO

Code:

S46559

Measures:

170 x 140 mm

Year:

1517 ca.

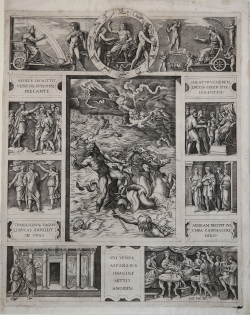

Solomon and the Queen of Sheba

Marcantonio RAIMONDI

Code:

S36091

Measures:

567 x 467 mm

Year:

1518 ca.

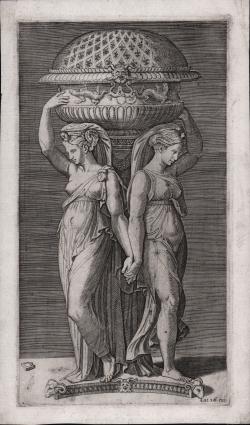

A Censer ("The Scent Box of François I")

Marcantonio RAIMONDI

Code:

S42520

Measures:

219 x 324 mm

Year:

1518 ca.

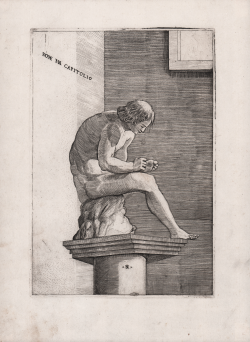

The Spinario

Marco DENTE detto "Marco da Ravenna"

Code:

S47036

Measures:

170 x 250 mm

Year:

1520 ca.

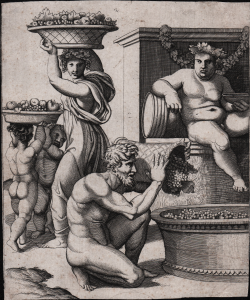

Silenus Supported by a Young Bacchant

Marcantonio RAIMONDI

Code:

S39708

Measures:

137 x 270 mm

Year:

1520 ca.

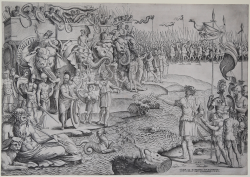

Scipio and Hannibal

Marco DENTE detto "Marco da Ravenna"

Code:

S30313

Measures:

552 x 391 mm

Year:

1521 ca.