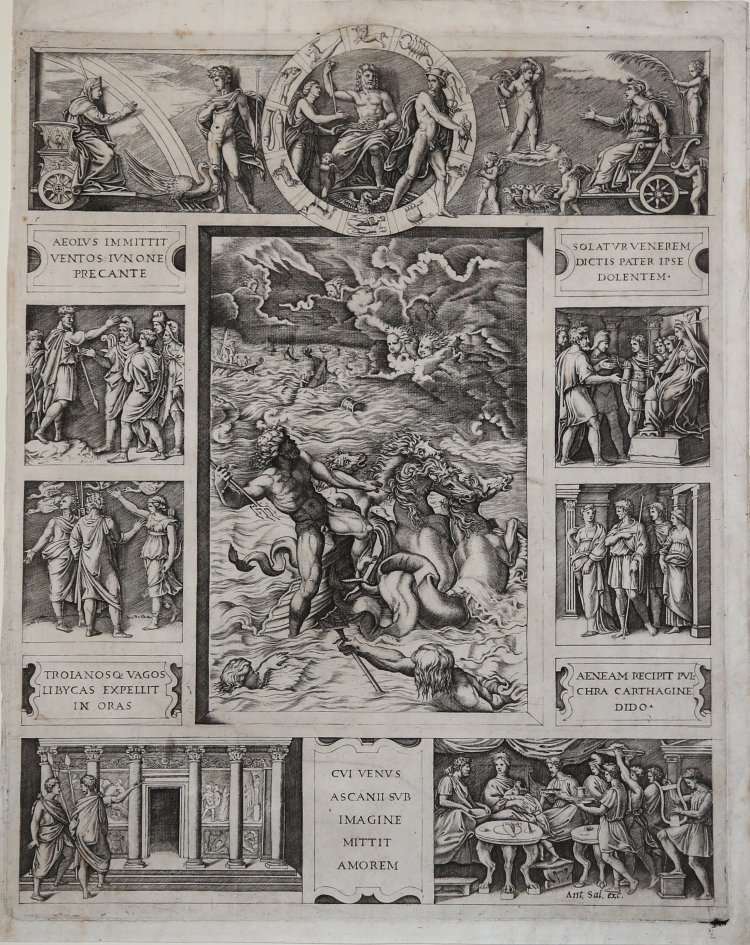

| Reference: | S36067 |

| Author | Marcantonio RAIMONDI |

| Year: | 1516 ca. |

| Measures: | 333 x 420 mm |

| Reference: | S36067 |

| Author | Marcantonio RAIMONDI |

| Year: | 1516 ca. |

| Measures: | 333 x 420 mm |

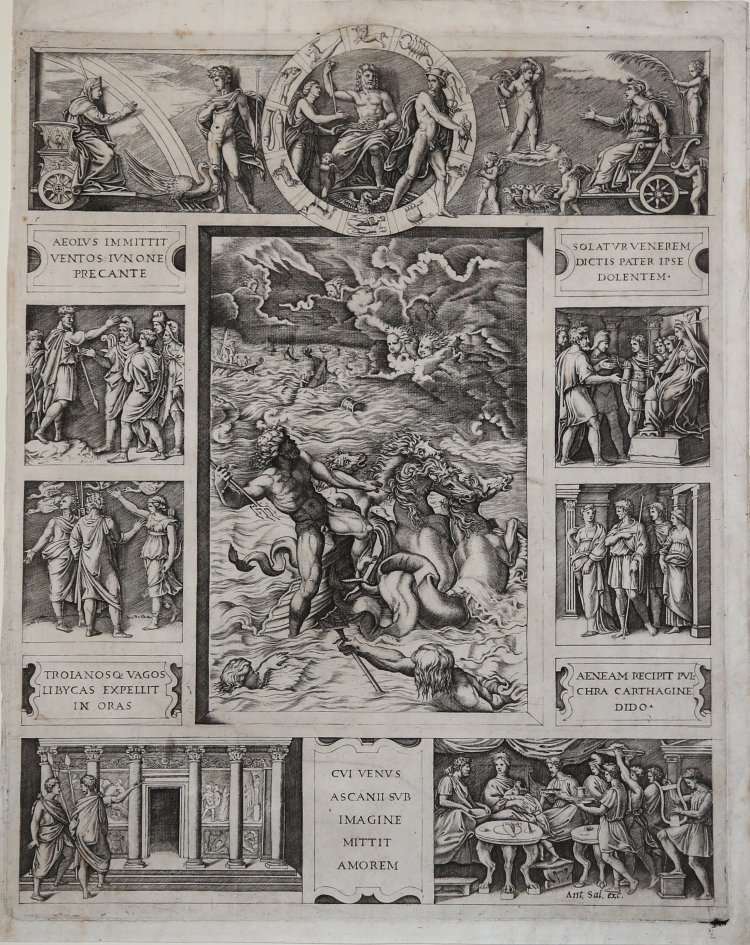

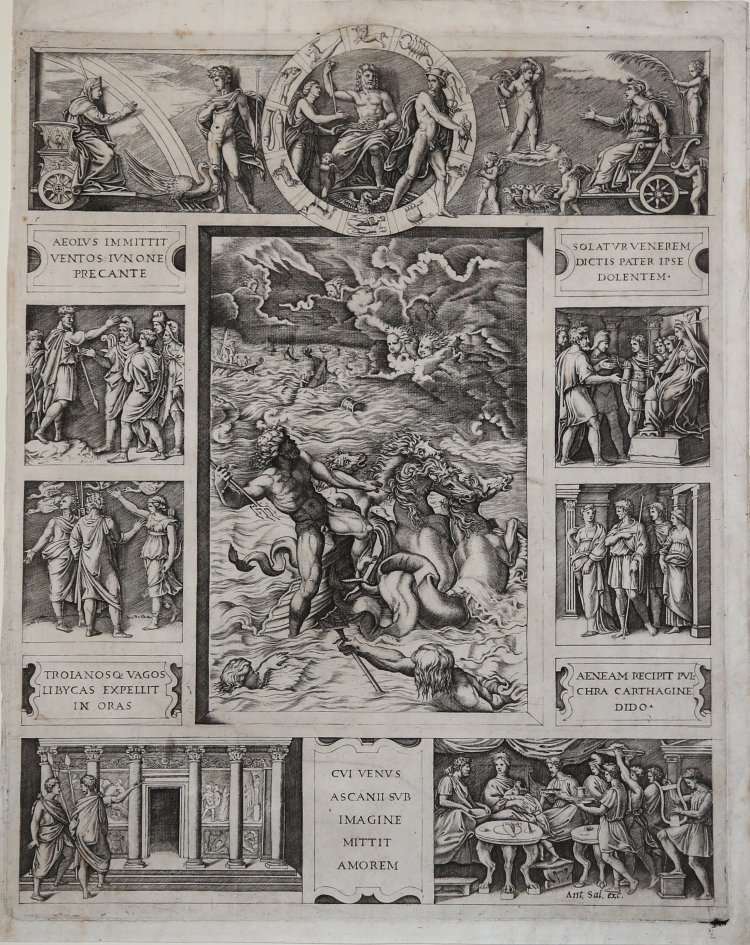

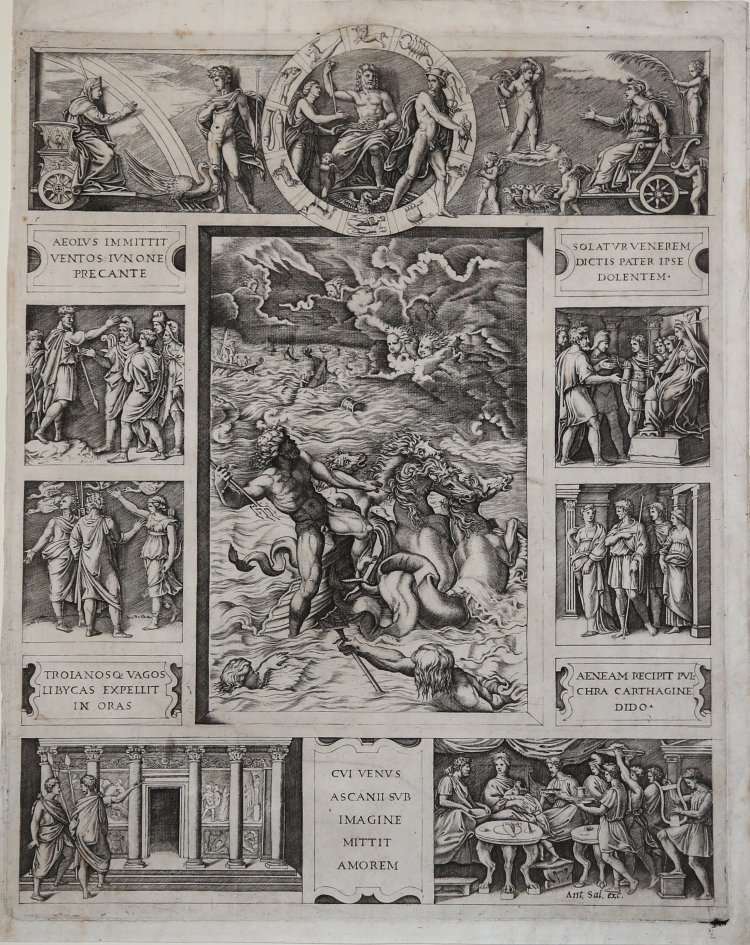

Engraving, about 1516. After Raphael.

Example of the second state of three, showing the address of Antonio Salamanca.

A very good impression, printed on contemporary laid paper with watermark "shield with star an letter M", with margins, some small tears repaired at the margins, otherwise in excellent condition.

Ambitious in terms of the subject matter and the complex compositional conception in the style of classical relief sculptures, this print is considered among the most important ones of Marcantonio Raimondi’s prolific career and one of his most accomplished examples of “ancient engraving”. In fact, the composition of the scenes is inspired by a relief dating to the first century A.D. known as the Tabula iliaca, a tablet illustrating scenes from the Iliad and the Odyssey in a series of small narrative panels arranged around a central scene.

“[…]it presents subjects from Book One of the Aeneid, particularly those that take place after the escape of Aeneas and his men from Troy and before their departure from Carthage. The central scene of Quos Ego, and its eponymous subject, is that moment at the beginning of the poem when Neptune commandingly calms a storm in order to procure Aeneas’s passage to the shores of North Africa. The surrounding scenes represent the circumstances and the deeds that follow thereupon. On the upper left, we see Juno ordering Aeolus, god of the winds, to wreak havoc on the Trojan ships. In the central roundel, Venus implores the enthroned Jupiter to help her son, Aeneas, and the Trojans, with Mercury departing to deliver Jupiter’s help. On the upper right, Venus sends Cupid to lend additional support to Aeneas. On the left frame flanking the Neptune scene, we see Aeneas consoling the men who have survived the storm, Aeneas’s conversation with his mother, and, at the bottom left, Aeneas and Achates admiring paintings of the Trojan War on the walls of Juno’s temple in Carthage. In the small spaces to the right of the Neptune scene we see the Trojans in Dido’s throne room, then Dido leading Aeneas to a banquet, and at the bottom right, Dido, Aeneas, and Cupid, here dis-guised as Ascanius, dining together. It is during this feast that Dido falls in love with Aeneas by means of the wiles of Cupid, thus setting the stage for their tragic rupture. […]

Quos Ego is only one in a group of prints by Raphael and Marcantonio that present episodes from the Aeneid, some of which are among the most famous in the Raphael–Marcantonio œuvre. […]

Of course, the striking artificiality of the frame is further emphasized by Raphael’s adoption of all’antica style for its scenes and inscriptions. The scenes of the frame, after all, are portrayed according to the model of Antonine relief sculpture that Raphael was studying at this time in Rome. In the spirit of his precocious art historical researches, Raphael does not project his figurations into anything like believable, perspectivally correct settings, but rather places them, in the manner of Roman reliefs, among disproportionately small props standing for doorways and buildings. […]

Yet, Raphael’s most brilliant all’antica gesture was to organize the whole print in accord with the example of the tabula iliaca, a type of classical stone carving that depicted Homeric and Virgilian episodes in compartments around a larger scene. By organizing his scenes according to this framework, Raphael not only emulated antique artistic example, but also took advantage of a structural homology between the sculptural tabula and the theoretical ideal of the window-like image. In this way, Raphael lent classical weight to a contemporary concept of painting, underlining that what we see through it looks like an actual view into profound depth: Neptune’s sea is a realm of direct, sensate impressions. It is, in sum, a painting.”

Christian Kleinbub, "Raphael's 'Quos Ego': Forgotten Document of the Renaissance 'Paragone', Word and Image 28, no. 3 (Nov. 2012), 287-301

|

Bartsch 352 II/III, Delaborde 102; Oberhuber, Roma e lo stile classico di Raffaello, p. 299.

|

Marcantonio RAIMONDI (Sant'Andrea in Argine 1480 circa - Bologna 1534)

|

Marcantonio Raimondi is considered the greatest engraver of early Renaissance and the first to spread the work of Raphael. He was born in San’Andrea in Argine, near Bologna. His first artistic apprenticeship took place in Bologna, around 1504, in the workshop of Francesco Francia, painter and goldsmith.

His first known engraving is dated 1505. In 1506 he went to Venice to live and work; in this year, he started developing his own personal style for, in his production of that period, is quite evident the influence of Mantegna and Dürer. According to Vasari, Raimondi met Dürer in Venice, for they were both living there at the same time, but they had a quarrel over the reproductions, on copper, of Dürer’s seventeen woodcuts of the Vita della Vergine. After 1507, he turned to different models, especially those coming from Rome and Florence. He was in Rome in 1509, where he was introduced into the circle of the most important artists working in the City, such as Jacopo Rimanda from Bologna. In the same year he met Rapahel in the workshop of Baviera; the following year Raimondi became popular as the main interpreter of Raphael’s paintings. The Lucrezia can be considered the starting point of their cooperation and a sort of second beginning for Raimondi’s new style. In any case, together with the engravings representing Raphael’s works, Raimondi went on with the publication of his own subjects, especially antiquity, whose influence can be seen in his whole production (cfr. Dubois-Reymond 1978).

Between 1515-1516 Marcantonio started showing a keen interest for chiaroscuro, maybe under the influence fo Agostino Veneziano and Marco Dente, from Baviera’s workshop.

Till Raphael’s death, in 1520, Raimondi worked and lived in the background of the great artist from Urbino and engraved his works and those of his scholars.

His business went down after the Sacco (sack) Di Roma in 1527, when he was obliged to pay a huge amount of money to the invaders of the City to save his life.

He died in Bologna before 1534, in complete misery.

|

|

Bartsch 352 II/III, Delaborde 102; Oberhuber, Roma e lo stile classico di Raffaello, p. 299.

|

Marcantonio RAIMONDI (Sant'Andrea in Argine 1480 circa - Bologna 1534)

|

Marcantonio Raimondi is considered the greatest engraver of early Renaissance and the first to spread the work of Raphael. He was born in San’Andrea in Argine, near Bologna. His first artistic apprenticeship took place in Bologna, around 1504, in the workshop of Francesco Francia, painter and goldsmith.

His first known engraving is dated 1505. In 1506 he went to Venice to live and work; in this year, he started developing his own personal style for, in his production of that period, is quite evident the influence of Mantegna and Dürer. According to Vasari, Raimondi met Dürer in Venice, for they were both living there at the same time, but they had a quarrel over the reproductions, on copper, of Dürer’s seventeen woodcuts of the Vita della Vergine. After 1507, he turned to different models, especially those coming from Rome and Florence. He was in Rome in 1509, where he was introduced into the circle of the most important artists working in the City, such as Jacopo Rimanda from Bologna. In the same year he met Rapahel in the workshop of Baviera; the following year Raimondi became popular as the main interpreter of Raphael’s paintings. The Lucrezia can be considered the starting point of their cooperation and a sort of second beginning for Raimondi’s new style. In any case, together with the engravings representing Raphael’s works, Raimondi went on with the publication of his own subjects, especially antiquity, whose influence can be seen in his whole production (cfr. Dubois-Reymond 1978).

Between 1515-1516 Marcantonio started showing a keen interest for chiaroscuro, maybe under the influence fo Agostino Veneziano and Marco Dente, from Baviera’s workshop.

Till Raphael’s death, in 1520, Raimondi worked and lived in the background of the great artist from Urbino and engraved his works and those of his scholars.

His business went down after the Sacco (sack) Di Roma in 1527, when he was obliged to pay a huge amount of money to the invaders of the City to save his life.

He died in Bologna before 1534, in complete misery.

|