| Reference: | S36175 |

| Author | William Hamilton - Pietro FABRIS |

| Year: | 1776 ca. |

| Zone: | Vesuvius |

| Printed: | Naples |

| Measures: | 396 x 216 mm |

| Reference: | S36175 |

| Author | William Hamilton - Pietro FABRIS |

| Year: | 1776 ca. |

| Zone: | Vesuvius |

| Printed: | Naples |

| Measures: | 396 x 216 mm |

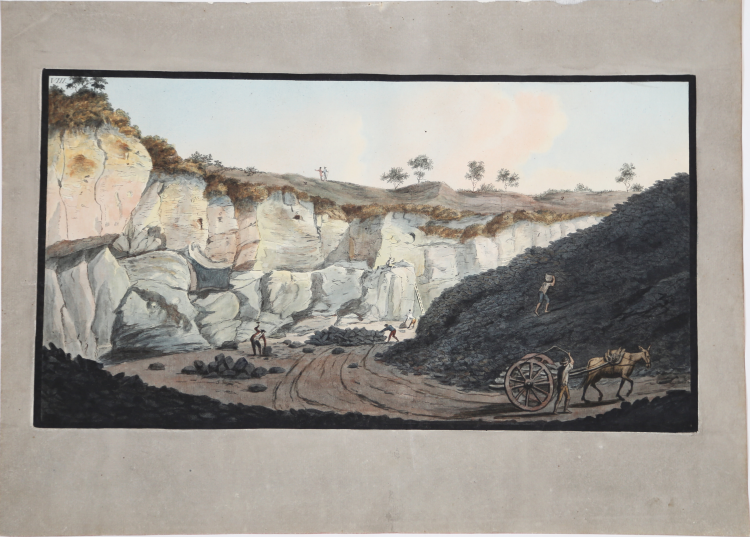

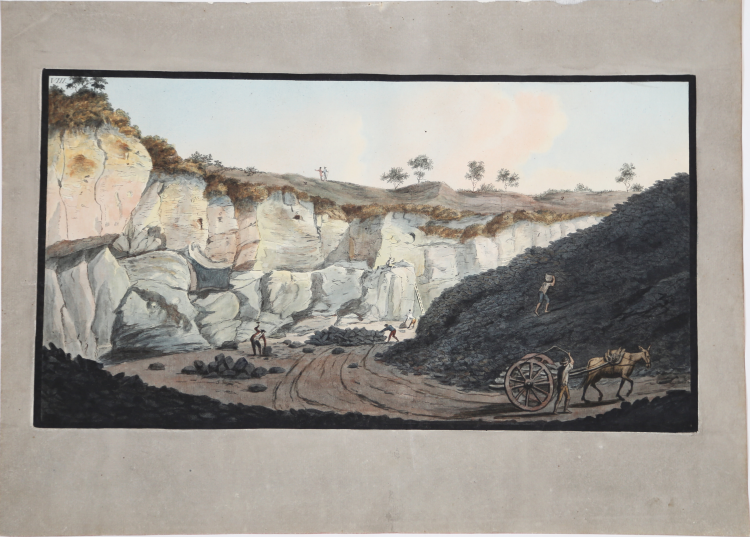

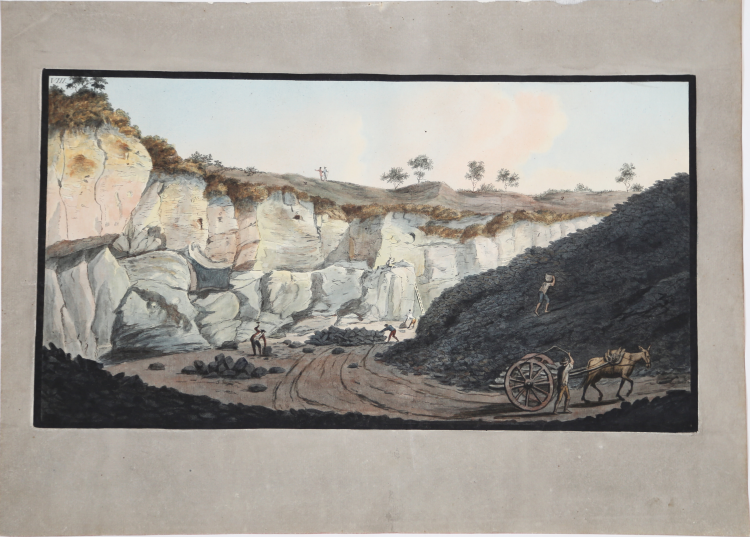

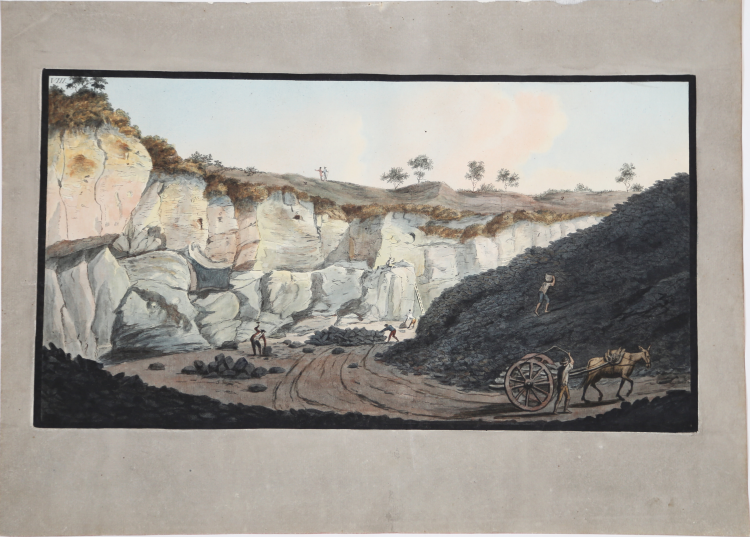

Plate taken from Campi Phlegraei. Observations on the Volcanos of the two Sicilies as They have been communicated to the Royal Society of London. Naples: sold by Pietro Fabris, 1776-1779.

Although Hamilton’s Observations on Mount Vesuvius (published by the Royal Society in 1772) was well-received at the time and ran to three editions, the Campi Phlegraei is the best known of Hamilton's four works on volcanic activity, and provided a clearer, more precise and useful explanation of volcanic activity than ever published before, which underlined Hamilton’s own theories about volcanoes being creative forces and enabled him to answer in one publication the lists of questions about volcanoes and rocks he had been receiving from correspondents all over Europe.

“Its publication in French and English provided it with a market not only in his own country but throughout Europe as well, and an international audience for a British discovery” (Jenkin and Sloan).

Pietro Fabris (fl.1756-1784), an artist living in Naples, was commissioned and trained by Hamilton to sketch the volcanoes of southern Italy. In four years Hamilton climbed Vesuvius at least twenty-two times, sometimes at great risk, since both he and Fabris wished to make sketches at every stage of the eruptions (the figures of Hamilton, often wearing a red coat, and Fabris, in blue, appear in the plates).

The plates are so opaquely colored that the engraved base beneath is hardly visible: indeed, Hamilton himself describes them as “executed with such delicacy and perfection, as scarcely to be distinguished from the original drawings themselves” (Part I, p. 6). Hamilton then asked Fabris to undertake the publication of his letters to the Royal Society, to be illustrated by engravings after the original drawings.

Fabris was the sole distributor of the work, which was originally published at 60 Neapolitan ducats for Part I and Part II; the price of the Supplement is not recorded.

Copperplate with fine original colour, mint condition.

|

Brunet III, 31 ("Ouvrage curieux et bien exicut"); ESTC T71231 (parts I-II); I. Jenkins and K. Sloan Vases and Volcanoes (London: 1996), "Catalogue" 43; Lewine p.232; Lowndes II, p.989.

|

William Hamilton - Pietro FABRIS

|

Pietro Fabris (active in Naples 1759 - 1779) was an Italian painter and engraver. He worked in Naples for most of his life, but frequently added the phrase ‘English painter’ to his signature. His genre scenes and landscapes, of which the earliest are four large canvases of Scenes of Popular Life (1756–7; Naples, priv. col.), illustrate events at the royal court as well as picturesque scenes of Neapolitan life with pedlars, fishermen, picnickers and dancers; they were popular with those making the Grand Tour. Two paintings representing the Departure of Charles III of Bourbon for Spain (Aranjuez, Pal. Real) were presumably painted in 1759, when this event occurred. In 1768 Fabris exhibited in London at the Free Society and accompanied the British envoy, Sir William Hamilton, to Sicily; he included a portrait of this enthusiastic patron in one of two genre scenes showing the Drawing-room in Lord Fortrose’s Apartment in Naples (1770; Edinburgh, N.P.G.). He exhibited again in London in 1772 at the Society of Artists.

Sir William Hamilton (Henley-on-Thames, 13 dicembre 1730 – Londra, 6 aprile 1803) was a Scottish diplomat, antiquarian, archaeologist and vulcanologist. After a short period as a Member of Parliament, he served as British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples from 1764 to 1800. He studied the volcanoes Vesuvius and Etna, becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society and recipient of the Copley Medal. Hamilton arrived in Naples on 17 November 1764 with the official title of Envoy Extraordinary to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and would remain as ambassador to the court of Ferdinand and Maria Carolina until 1800, although from November 1798 he was based in Palermo, the court having moved there when Naples was threatened by the French Army. As ambassador, Hamilton was expected to send reports back to the Secretary of State every ten days or so, to promote Britain's commercial interests in Naples, and to keep open house for English travellers to Naples. These official duties left him plenty of time to pursue his interests in art, antiquities, and music, as well as developing new interests in volcanoes and earthquakes. Catherine, who had never enjoyed good health, began to recover in the mild climate of Naples. Their main residence was the Palazzo Sessa, where they hosted official functions and where Hamilton housed his growing collection of paintings and antiquities; they also had a small villa on the seashore at Posillipo (later it would be called Villa Emma), a house at Portici, Villa Angelica, from where he could study Mount Vesuvius, and a house at Caserta near the Royal Palace.

Hamilton began collecting Greek vases and other antiquities as soon as he arrived in Naples, obtaining them from dealers or other collectors, or even opening tombs himself. In 1766–67 he published a volume of engravings of his collection entitled Collection of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman antiquities from the cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton, His Britannick Maiesty's envoy extraordinary at the Court of Naples. The text was written by d'Hancarville with contributions by Johann Winckelmann. A further three volumes were produced in 1769–76. During the his first leave in 1771 Hamilton arranged the sale of his collection to the British Museum for £8,400. Josiah Wedgwood the potter drew inspiration from the reproductions in Hamilton's volumes. During this first leave, in January 1772, Hamilton became a Knight of the Order of the Bath and the following month was elected Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. In 1777, during his second leave to England, he became a member of the Society of Dilettanti. When Hamilton returned to England for a third period of leave, in 1783–84, he brought with him a Roman glass vase, which had once belonged to the Barberini family and which later became known as the Portland Vase. Hamilton had bought it from a dealer and sold it to the Duchess of Portland. The cameo work on the vase again served as inspiration to Josiah Wedgwood, this time for his jasperware. The vase was eventually bought by the British Museum. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1792.

In 1798, as Hamilton was about to leave Naples, he packed up his art collection and a second vase collection and sent them back to England. A small part of the second vase collection went down with HMS Colossus off the Scilly Isles. The surviving part of the second collection was catalogued for sale at auction at Christie's when at the eleventh hour Thomas Hope stepped in and purchased the collection of mostly South Italian vases.

Soon after Hamilton arrived in Naples, Mount Vesuvius began to show signs of activity and in the summer of 1766 he sent an account of an eruption, together with drawings and samples of salts and sulphurs, to the Royal Society in London. On the strength of this paper he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the autumn of 1767 there was an even greater eruption and again Hamilton sent a report to the Royal Society. The two papers were published as an article in the Society's journal Philosophical Transactions.

The Royal Society awarded him the Copley Medal in 1770 for his paper, "An Account of a Journey to Mount Etna". In 1772 he published his writings on both volcanoes in a volume called Observations on Mount Vesuvius, Mount Etna, and other volcanos. This was followed in 1776 by a collection of his letters on volcanoes, entitled Campi Phlegraei (Flaming fields, the name given by the Ancients to the area around Naples). The volume was illustrated by Pietro Fabris.

Hamilton was also interested in earthquakes. He visited Calabria and Messina after the earthquake of 1783 and wrote a paper for the Royal Society

|

|

Brunet III, 31 ("Ouvrage curieux et bien exicut"); ESTC T71231 (parts I-II); I. Jenkins and K. Sloan Vases and Volcanoes (London: 1996), "Catalogue" 43; Lewine p.232; Lowndes II, p.989.

|

William Hamilton - Pietro FABRIS

|

Pietro Fabris (active in Naples 1759 - 1779) was an Italian painter and engraver. He worked in Naples for most of his life, but frequently added the phrase ‘English painter’ to his signature. His genre scenes and landscapes, of which the earliest are four large canvases of Scenes of Popular Life (1756–7; Naples, priv. col.), illustrate events at the royal court as well as picturesque scenes of Neapolitan life with pedlars, fishermen, picnickers and dancers; they were popular with those making the Grand Tour. Two paintings representing the Departure of Charles III of Bourbon for Spain (Aranjuez, Pal. Real) were presumably painted in 1759, when this event occurred. In 1768 Fabris exhibited in London at the Free Society and accompanied the British envoy, Sir William Hamilton, to Sicily; he included a portrait of this enthusiastic patron in one of two genre scenes showing the Drawing-room in Lord Fortrose’s Apartment in Naples (1770; Edinburgh, N.P.G.). He exhibited again in London in 1772 at the Society of Artists.

Sir William Hamilton (Henley-on-Thames, 13 dicembre 1730 – Londra, 6 aprile 1803) was a Scottish diplomat, antiquarian, archaeologist and vulcanologist. After a short period as a Member of Parliament, he served as British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples from 1764 to 1800. He studied the volcanoes Vesuvius and Etna, becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society and recipient of the Copley Medal. Hamilton arrived in Naples on 17 November 1764 with the official title of Envoy Extraordinary to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and would remain as ambassador to the court of Ferdinand and Maria Carolina until 1800, although from November 1798 he was based in Palermo, the court having moved there when Naples was threatened by the French Army. As ambassador, Hamilton was expected to send reports back to the Secretary of State every ten days or so, to promote Britain's commercial interests in Naples, and to keep open house for English travellers to Naples. These official duties left him plenty of time to pursue his interests in art, antiquities, and music, as well as developing new interests in volcanoes and earthquakes. Catherine, who had never enjoyed good health, began to recover in the mild climate of Naples. Their main residence was the Palazzo Sessa, where they hosted official functions and where Hamilton housed his growing collection of paintings and antiquities; they also had a small villa on the seashore at Posillipo (later it would be called Villa Emma), a house at Portici, Villa Angelica, from where he could study Mount Vesuvius, and a house at Caserta near the Royal Palace.

Hamilton began collecting Greek vases and other antiquities as soon as he arrived in Naples, obtaining them from dealers or other collectors, or even opening tombs himself. In 1766–67 he published a volume of engravings of his collection entitled Collection of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman antiquities from the cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton, His Britannick Maiesty's envoy extraordinary at the Court of Naples. The text was written by d'Hancarville with contributions by Johann Winckelmann. A further three volumes were produced in 1769–76. During the his first leave in 1771 Hamilton arranged the sale of his collection to the British Museum for £8,400. Josiah Wedgwood the potter drew inspiration from the reproductions in Hamilton's volumes. During this first leave, in January 1772, Hamilton became a Knight of the Order of the Bath and the following month was elected Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. In 1777, during his second leave to England, he became a member of the Society of Dilettanti. When Hamilton returned to England for a third period of leave, in 1783–84, he brought with him a Roman glass vase, which had once belonged to the Barberini family and which later became known as the Portland Vase. Hamilton had bought it from a dealer and sold it to the Duchess of Portland. The cameo work on the vase again served as inspiration to Josiah Wedgwood, this time for his jasperware. The vase was eventually bought by the British Museum. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1792.

In 1798, as Hamilton was about to leave Naples, he packed up his art collection and a second vase collection and sent them back to England. A small part of the second vase collection went down with HMS Colossus off the Scilly Isles. The surviving part of the second collection was catalogued for sale at auction at Christie's when at the eleventh hour Thomas Hope stepped in and purchased the collection of mostly South Italian vases.

Soon after Hamilton arrived in Naples, Mount Vesuvius began to show signs of activity and in the summer of 1766 he sent an account of an eruption, together with drawings and samples of salts and sulphurs, to the Royal Society in London. On the strength of this paper he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the autumn of 1767 there was an even greater eruption and again Hamilton sent a report to the Royal Society. The two papers were published as an article in the Society's journal Philosophical Transactions.

The Royal Society awarded him the Copley Medal in 1770 for his paper, "An Account of a Journey to Mount Etna". In 1772 he published his writings on both volcanoes in a volume called Observations on Mount Vesuvius, Mount Etna, and other volcanos. This was followed in 1776 by a collection of his letters on volcanoes, entitled Campi Phlegraei (Flaming fields, the name given by the Ancients to the area around Naples). The volume was illustrated by Pietro Fabris.

Hamilton was also interested in earthquakes. He visited Calabria and Messina after the earthquake of 1783 and wrote a paper for the Royal Society

|