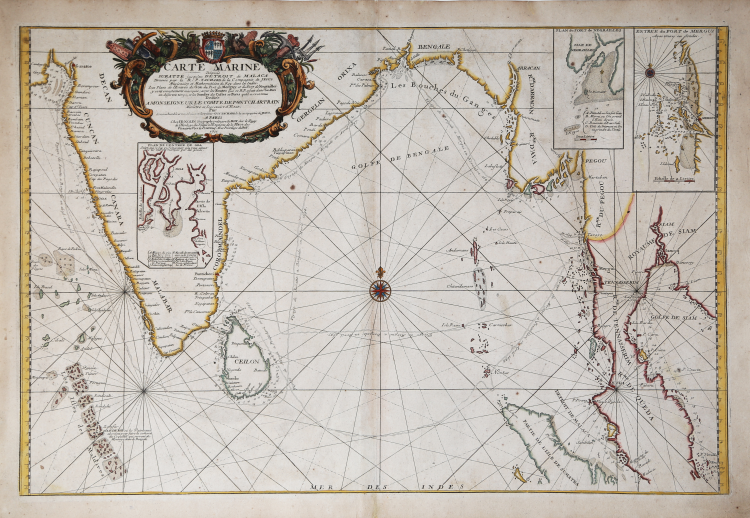

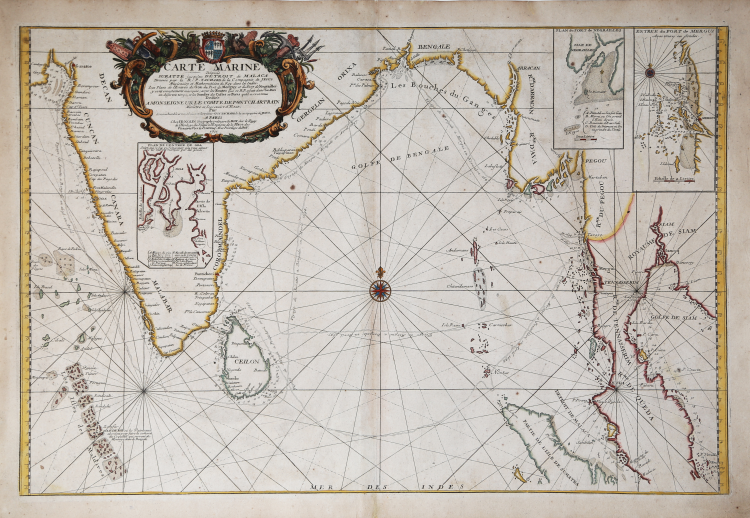

| Reference: | S33971 |

| Author | Jean Baptiste NOLIN |

| Year: | 1701 |

| Zone: | Indian Ocean |

| Printed: | Paris |

| Measures: | 730 x 487 mm |

| Reference: | S33971 |

| Author | Jean Baptiste NOLIN |

| Year: | 1701 |

| Zone: | Indian Ocean |

| Printed: | Paris |

| Measures: | 730 x 487 mm |

Rare and important chart of the Indian Ocean, illustrating the route of the Jesuit priest Guy Tachard in 1697.

The map extends to show the Maldives, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), much of India, the flood plains of the Ganges River, Burma, and continuing around to Malacca on the Malaysian Peninsula. Shows most of Sumatra and names the Aceh region. Three insets detail the vicinity of Goa, the Port of Negrailles, and the Port of Mergui in Burma.

Copper engraving with fine later hand colour, in very good condition.

Guy Tachard (1651–1712), was a Jesuit missionary and mathematician, who made 2 embassy's to the Kingdom of Siam for King Louis XIV. Taachard was first sent to Siam in 1685 with five other Jesuits under Superior Jean de Fontaney, on an embassy to Siam led by Chevalier de Chaumont and François-Timoléon de Choisy, and accompanied by Claude de Forbin. The objective of the Jesuits was to complete a scientific expedition to the Indies and China. Enticed by the Greek Constantine Phaulkon, he returned to France to suggest an alliance with the king of Siam Narai to Louis XIV.

The two ships of the embassy returned to France with a Siamese embassy, led by the Siamese ambassador Kosa Pan, who was bringing a proposal for an eternal alliance between France and Siam. The embassy stayed in France from June 1686 to March 1687.

Tachard joined the second embassy to Siam in March 1687, organized by Colbert. The embassy consisted in five warships, led by General Desfarges, in part to return with the members of Siamese embassy. The mission was led by Simon de la Loubère and Claude Céberet du Boullay, director of the French East India Company. The disambarkment of French troops in Bangkok and Mergui led to strong nationalistic movements in Siam directed by Phra Petratcha, and ultimately resulted in the 1688 Siamese revolution in which king Narai died, Phaulkon was executed, and Phra Petratcha became king.

Desfarges negotiated to return with his men to Pondicherry. In the later part of 1689, Desfarges captured the island of Phuket in an attempt to restore French control. Tachard, with Siamese envoys, translating the letter of king Narai to Pope Innocent XI, December 1688.

Meanwhile Tachard returned to France with the title of "Ambassador Extraordinary for the King of Siam", accompanied by Ok-khun Chamnan, and visited the Vatican in January 1688. He and his Siamese embassy met with Pope Innocent XI and translated Narai's letter to him.

In 1690, when Tachard tried to return to Siam, a revolution had happened, King Narai was already dead, and a new king was on the throne. Tachard had to stop at Pondicherry and return to France without obtaining a permission to enter the country.

In 1697, Tachard again went to Siam, and managed to enter the country this time. He met with Kosa Pan, now Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and the new king Petracha, but the meeting did not result in any significant agreements.

Jean Baptiste NOLIN (circa 1657 - 1708)

|

Jean-Baptiste Nolin (ca. 1657-1708) was a French engraver who worked at the turn of the eighteenth century. Initially trained by Francois de Poilly, his artistic skills caught the eye of Vincenzo Coronelli when the latter was working in France. Coronelli encouraged the young Nolin to engrave his own maps, which he began to do.

Whereas Nolin was a skilled engraver, he was not an original geographer. He also had a flair for business, adopting monikers like the Geographer to the Duke of Orelans and Engerver to King XIV. He, like many of his contemporaries, borrowed liberally from existing maps. In Nolin’s case, he depended especially on the works of Coronelli and Jean-Nicholas de Tralage, the Sieur de Tillemon. This practice eventually caught Nolin in one of the largest geography scandals of the eighteenth century.

In 1700, Nolin published a large world map which was seen by Claude Delisle, father of the premier mapmaker of his age, Guillaume Delisle. Claude recognized Nolin’s map as being based in part on his son’s work. Guillaume had been working on a manuscript globe for Louis Boucherat, the chancellor of France, with exclusive information about the shape of California and the mouth of the Mississippi River. This information was printed on Nolin’s map. The court ruled in the Delisles’ favor after six years. Nolin had to stop producing that map, but he continued to make others.

Calling Nolin a plagiarist is unfair, as he was engaged in a practice that practically every geographer adopted at the time. Sources were few and copyright laws weak or nonexistent. Nolin’s maps are engraved with considerable skill and are aesthetically engaging.

Nolin’s son, also Jean-Baptiste (1686-1762), continued his father’s business.

|

Jean Baptiste NOLIN (circa 1657 - 1708)

|

Jean-Baptiste Nolin (ca. 1657-1708) was a French engraver who worked at the turn of the eighteenth century. Initially trained by Francois de Poilly, his artistic skills caught the eye of Vincenzo Coronelli when the latter was working in France. Coronelli encouraged the young Nolin to engrave his own maps, which he began to do.

Whereas Nolin was a skilled engraver, he was not an original geographer. He also had a flair for business, adopting monikers like the Geographer to the Duke of Orelans and Engerver to King XIV. He, like many of his contemporaries, borrowed liberally from existing maps. In Nolin’s case, he depended especially on the works of Coronelli and Jean-Nicholas de Tralage, the Sieur de Tillemon. This practice eventually caught Nolin in one of the largest geography scandals of the eighteenth century.

In 1700, Nolin published a large world map which was seen by Claude Delisle, father of the premier mapmaker of his age, Guillaume Delisle. Claude recognized Nolin’s map as being based in part on his son’s work. Guillaume had been working on a manuscript globe for Louis Boucherat, the chancellor of France, with exclusive information about the shape of California and the mouth of the Mississippi River. This information was printed on Nolin’s map. The court ruled in the Delisles’ favor after six years. Nolin had to stop producing that map, but he continued to make others.

Calling Nolin a plagiarist is unfair, as he was engaged in a practice that practically every geographer adopted at the time. Sources were few and copyright laws weak or nonexistent. Nolin’s maps are engraved with considerable skill and are aesthetically engaging.

Nolin’s son, also Jean-Baptiste (1686-1762), continued his father’s business.

|