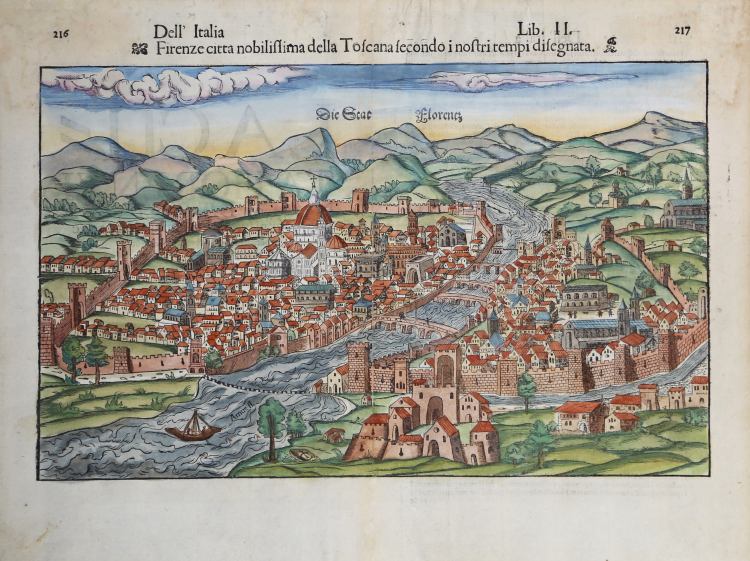

| Reference: | S19118 |

| Author | Sebastian Münster |

| Year: | 1550 ca. |

| Zone: | Florence |

| Printed: | Basle |

| Measures: | 360 x 225 mm |

| Reference: | S19118 |

| Author | Sebastian Münster |

| Year: | 1550 ca. |

| Zone: | Florence |

| Printed: | Basle |

| Measures: | 360 x 225 mm |

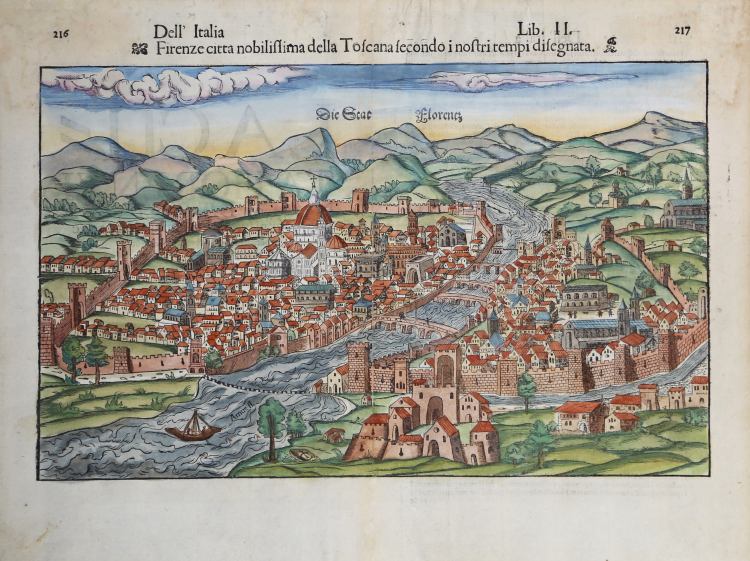

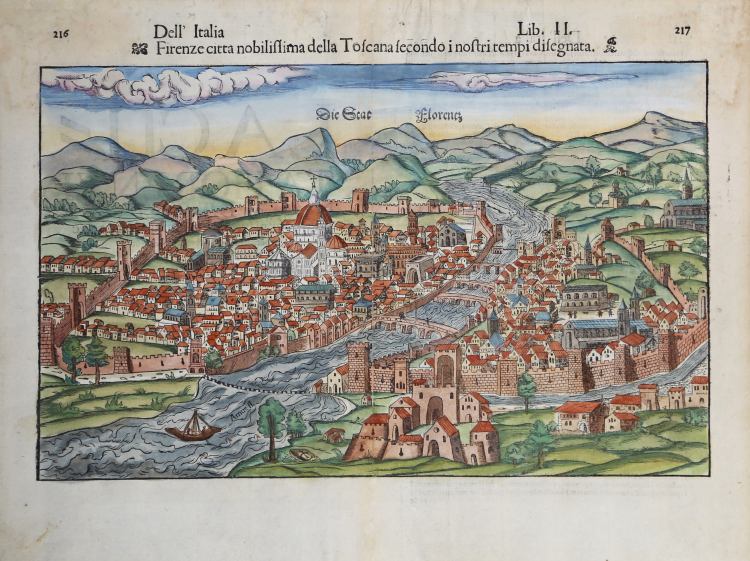

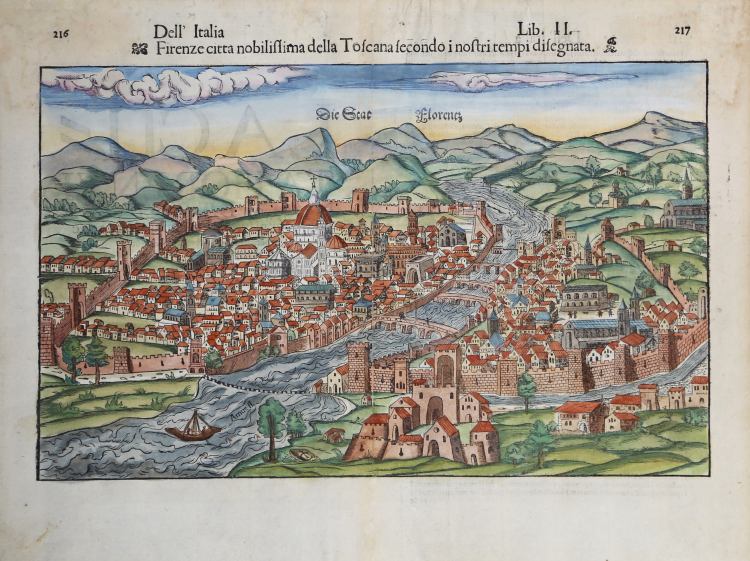

View of Florence from Monte Oliveto, based on the model introduced by Francesco Rosselli in the late 15th century, the so called Veduta della Catena (view with the chain). Plate taken from the Cosmographiae Universalis, the rare Italian edition, Basel, second half of the 16th Century. Based on the Francesco Rosselli's Veduta della Catena.

The Cosmographiae Universalis of Sebastian Münster (1488-1552), printed for the first time in Basel in 1544 by the publisher Heinrich Petri, was updated several times and increased with new maps and urban representations in its many editions until the beginning of the next century. Münster had worked to collect information in order to obtain a work that did not disappoint expectations and, after a further publication in German embellished with 910 woodblock prints, arrived in 1550 to the final edition in Latin, illustrated by 970 woodcuts.

There were then numerous editions in different languages, including Latin, French, Italian, English and Czech. After his death in Münster (1552), Heinrich Petri first, and then his son Sebastian, continued the publication of the work. The Cosmographia universalis was one of the most popular and successful books of the 16th century, and saw as many as 24 editions in 100 years: the last German edition was published in 1628, long after the author's death. The Cosmographia contained not only the latest maps and views of all the most famous cities, but also a series of encyclopedic details related to the known, and unknown, world.

The particular commercial success of this work was due in part to the beautiful engravings (among whose authors can be mentioned Hans Holbein the Younger, Urs Graf, Hans Rudolph Manuel Deutsch, David Kandel).

“La cosiddetta Veduta della Catena, è la prima rappresentazione conosciuta di una intera città, risultato non di una proiezione fantasiosa, ma di una costruzione che, basata sull’osservazione diretta dal vero, si avvale anche della prospettiva. Questa grande silografia, come ha dimostrato Hülsen, deriva dall’opera originale a bulino, su sei lastre di rame, attribuita a Francesco Rosselli, di cui oggi è conservato solo un frammento, raffigurante la campagna in direzione di Fiesole. La copia silografica, attribuita già da Kristeller a Luca Antonio degli Uberti è conservata presso il Gabinetto delle Stampe di Berlino. La silografia con ogni probabilità è stata realizzata nella prima decade del XVI secolo a Venezia, come indicato dal tratteggio a linee parallele nelle zone d’ombra, che si utilizza solo nella prima decade del sec. XVI. Rispetto al modello fiorentino, Lucantonio degli Uberti introduce due elementi innovativi: la figura dell’artista disegnatore, in basso a destra, e il motivo decorativo della catena, chiusa in alto a sinistra da un lucchetto – di qui la denominazione Veduta della Catena - per cui sono state fornite diverse interpretazioni. Il punto di osservazione principale è da sud-ovest, in corrispondenza del campanile della chiesa di Monte Oliveto, ed è stato rialzato per dare maggiore leggibilità alle emergenze architettoniche e al tessuto urbano. Nella veduta l’asse centrale verticale viene fatto coincidere con l’asse della cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore che, simbolo religioso e civile della città, diventa così elemento principale e punto costante di riferimento nella rappresentazione della città stessa. La veduta crea un campo spaziale continuo che non solo mostra gli edifici, ma anche gli spazi aperti, le piazze e anche il corso delle strade di recente realizzazione, e non ancora chiuse dagli edifici che saranno costruiti lungo i loro lati. I monumenti della città sono quindi disposti nella pianta in modo da riflettere le reali relazioni tra di loro. Fuori dalle mura della città, l’immagine restituisce le principali caratteristiche del paesaggio naturale: vista da sud-est, la pianta mostra la città delimitata a nord dalla parete naturale degli Appenini; la valle del Mugnone, attraverso la quale passa la strada che collega la città a Bologna, crea una spettacolare apertura tra le montagne nell’angolo superiore a sinistra. Fiesole e S. Domenico sono rappresentate con un gruppo di edifici sormontati dal toponimo. Il convento di S. Miniato e di S. Francesco segnano le vette che dominano la città da sud. L’Arno attraversa diagonalmente l’immagine tagliando la città in due parti. Dunque, la rappresentazione del paesaggio non è né evocativo né poetico. Questa rappresentazione senza soluzione di continuità tra la città, fulcro dell’immagine, e il paesaggio, risponde sia alla realtà politica, in quanto i territori rappresentati appartengono di fatto allo Stato fiorentino, sia ad un’ambizione pittorica: sia la città che il paesaggio circostante sono concepiti come uno spazio topografico unitario. La veduta riporta il titolo FIORENZA, variante poetica del toponimo che, come sottolinea David Friedman, fa allusione ai concetti di “fiore” e di “fioritura” e viene usata con intento celebrativo, collegata ai concetti di pace e prosperità” (cfr. Bifolco-Ronca, Cartografia e Topografia Italiana del XVI secolo, pp. 2148-2149)

Woodcut, beautiful hand-coloring, in good condition.

Sebastian Münster (1488 - 1552)

|

Sebastian Münster was a German cartographer, cosmographer, and Hebrew scholar whose Cosmographia (1544; "Cosmography") was the earliest German description of the world and a major work - after the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 - in the revival of geography in the 16th-century Europe. Altogether, about 40 editions of the Cosmographia appeared during 1544-1628. Although other cosmographies predate Münster's, he is given first place in historical discussions of this sort of publication, and was a major influence on his subject for over 200 years.

In nearly all works by Münster, his Cosmographia is given pride of place. Despite this, we still lack a detailed survey of its contents from edition to edition, along the years from 1544 to 1628, and an account of its influence on a wide range of scientific disciplines. Münster obtained the material for his book in three ways. He used all available literary sources. He tried to obtain original manuscript material for description of the countryside and of villages and towns. Finally, he obtained further material on his travels (primarily in south-west Germany, Switzerland, and Alsace). The Cosmographia contained not only the latest maps and views of many well-known cities, but included an encyclopaedic amount of details about the known - and unknown - world and undoubtedly must have been one of the most widely read books of its time.

Aside from the well-known maps and views present in the Cosmographia, the text is thickly sprinkled with vigorous woodcuts: portraits of kings and princes, costumes and occupations, habits and customs, flora and fauna, monsters and horrors. The 1614 and 1628 editions of Cosmographia are divided into nine books. Nearly all the sections, especially those dealing with history, were enlarged. Descriptions were extended, additional places included, errors rectified.

|

Sebastian Münster (1488 - 1552)

|

Sebastian Münster was a German cartographer, cosmographer, and Hebrew scholar whose Cosmographia (1544; "Cosmography") was the earliest German description of the world and a major work - after the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 - in the revival of geography in the 16th-century Europe. Altogether, about 40 editions of the Cosmographia appeared during 1544-1628. Although other cosmographies predate Münster's, he is given first place in historical discussions of this sort of publication, and was a major influence on his subject for over 200 years.

In nearly all works by Münster, his Cosmographia is given pride of place. Despite this, we still lack a detailed survey of its contents from edition to edition, along the years from 1544 to 1628, and an account of its influence on a wide range of scientific disciplines. Münster obtained the material for his book in three ways. He used all available literary sources. He tried to obtain original manuscript material for description of the countryside and of villages and towns. Finally, he obtained further material on his travels (primarily in south-west Germany, Switzerland, and Alsace). The Cosmographia contained not only the latest maps and views of many well-known cities, but included an encyclopaedic amount of details about the known - and unknown - world and undoubtedly must have been one of the most widely read books of its time.

Aside from the well-known maps and views present in the Cosmographia, the text is thickly sprinkled with vigorous woodcuts: portraits of kings and princes, costumes and occupations, habits and customs, flora and fauna, monsters and horrors. The 1614 and 1628 editions of Cosmographia are divided into nine books. Nearly all the sections, especially those dealing with history, were enlarged. Descriptions were extended, additional places included, errors rectified.

|