| Reference: | S41920 |

| Author | Henrick van SCHOEL |

| Year: | 1614 ca. |

| Zone: | Florence |

| Printed: | Rome |

| Measures: | 430 x 310 mm |

| Reference: | S41920 |

| Author | Henrick van SCHOEL |

| Year: | 1614 ca. |

| Zone: | Florence |

| Printed: | Rome |

| Measures: | 430 x 310 mm |

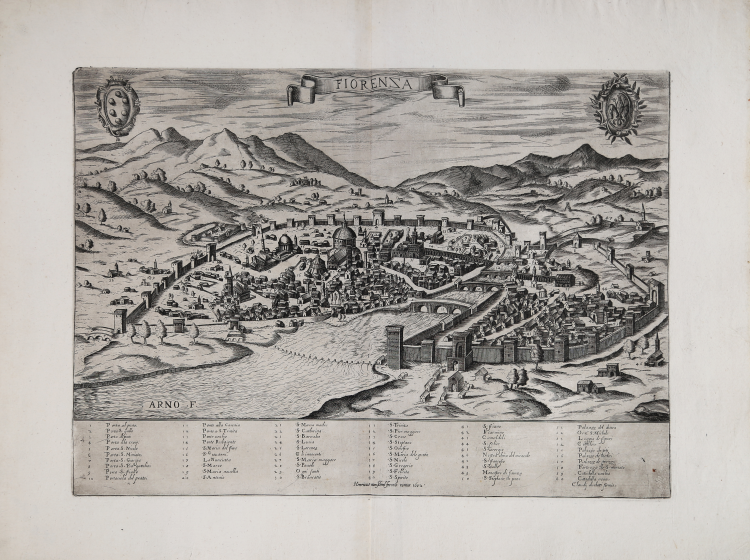

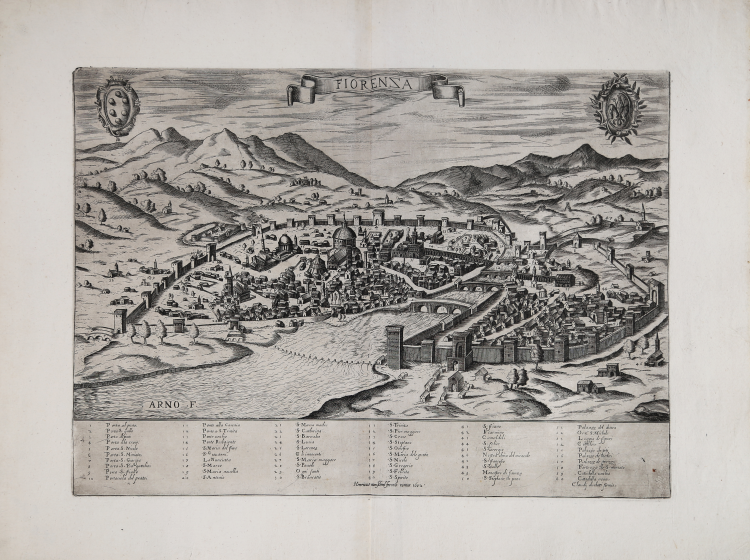

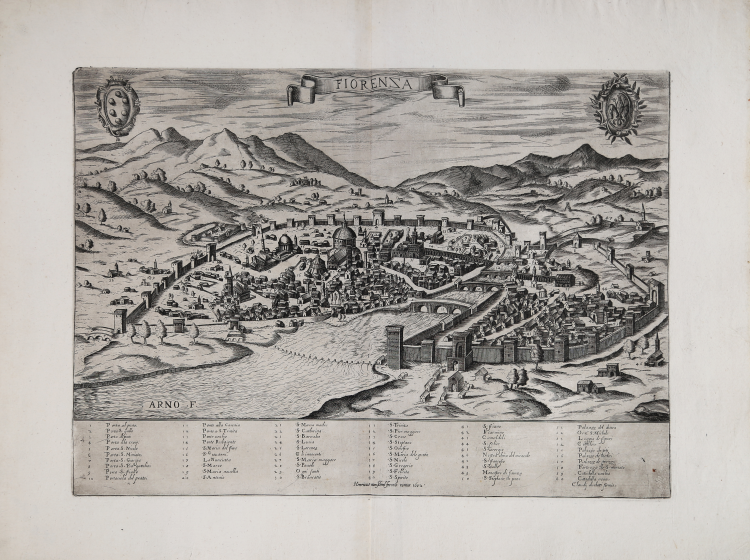

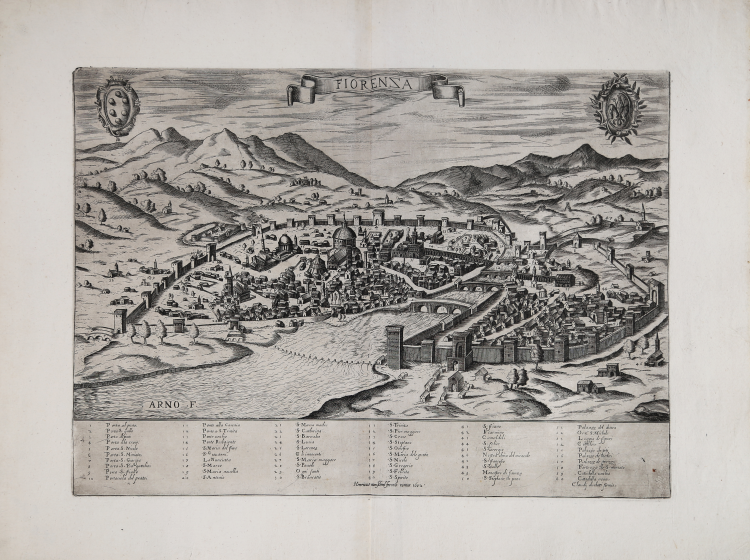

View of Florence from Monte Oliveto, based on the model introduced by Francesco Rosselli in the late 15th century, the so called Veduta della Catena (view with the chain). In the upper center, in a ribbon-shaped cartouche, we find the title: FIORENZA. On the upper left is the Medici family coat of arms, and on the right that of the city. Along the lower margin there is a numerical legend with 60 references to notable places and monuments, distributed over six columns. Follows the imprint editorial Claudij duchetti formis. Work without orientation and graphic scale.

Perspective view of the city, first Roman derivation of Francesco Rosselli's model, first published by Claudio Duchetti in about 1580. It is more likely that Duchetti replicated the view attributed to Paolo Forlani (1567), enlarging it and repeating the errors and deformations in the monuments. In the center, a ribbon cartouche with the title; in the left corner, a shield with the Medici coat of arms; on the right, a shield with the Florentine lily.

Example in the third state of four, with the imprint at the bottom Henricus van Schoel formis romae 1602.

“The plate was inherited by Giacomo Gherardi and is included in the catalog edited on behalf of his widow Quintilia Lucidi, October 17-19, 1598 (No. 349 described as "Fiorenza in a royal sheet"). It was then acquired, in 1602, by Giovanni Orlandi who reprinted it unchanged with the addition of his own imprint. In 1614, with the transfer of Orlandi in Naples, the plate was sold to Hendrick van Schoel, whose edition, however, still bears the date 1602. In the catalog of the printing house of the Flemish printer, drawn up on July 27, 1622 after the death of the publisher, the works of cartography described under one heading: " Cosmografia pezzi numero 80.ottanta”. The plates were then sold to Francesco de Paoli, as documented by the inventory of the sale of November 2, 1633. Possible then the existence of a further issue of this plate, of which, however, we have found no examples” (see Bifolco-Ronca, Cartografia e topografia italiana del XVI secolo, pp. 2156-2157).

“La cosiddetta Veduta della Catena, è la prima rappresentazione conosciuta di una intera città, risultato non di una proiezione fantasiosa, ma di una costruzione che, basata sull’osservazione diretta dal vero, si avvale anche della prospettiva. Questa grande silografia, come ha dimostrato Hülsen, deriva dall’opera originale a bulino, su sei lastre di rame, attribuita a Francesco Rosselli, di cui oggi è conservato solo un frammento, raffigurante la campagna in direzione di Fiesole. La copia silografica, attribuita già da Kristeller a Luca Antonio degli Uberti è conservata presso il Gabinetto delle Stampe di Berlino. La silografia con ogni probabilità è stata realizzata nella prima decade del XVI secolo a Venezia, come indicato dal tratteggio a linee parallele nelle zone d’ombra, che si utilizza solo nella prima decade del sec. XVI. Rispetto al modello fiorentino, Lucantonio degli Uberti introduce due elementi innovativi: la figura dell’artista disegnatore, in basso a destra, e il motivo decorativo della catena, chiusa in alto a sinistra da un lucchetto – di qui la denominazione Veduta della Catena - per cui sono state fornite diverse interpretazioni. Il punto di osservazione principale è da sud-ovest, in corrispondenza del campanile della chiesa di Monte Oliveto, ed è stato rialzato per dare maggiore leggibilità alle emergenze architettoniche e al tessuto urbano. Nella veduta l’asse centrale verticale viene fatto coincidere con l’asse della cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore che, simbolo religioso e civile della città, diventa così elemento principale e punto costante di riferimento nella rappresentazione della città stessa. La veduta crea un campo spaziale continuo che non solo mostra gli edifici, ma anche gli spazi aperti, le piazze e anche il corso delle strade di recente realizzazione, e non ancora chiuse dagli edifici che saranno costruiti lungo i loro lati. I monumenti della città sono quindi disposti nella pianta in modo da riflettere le reali relazioni tra di loro. Fuori dalle mura della città, l’immagine restituisce le principali caratteristiche del paesaggio naturale: vista da sud-est, la pianta mostra la città delimitata a nord dalla parete naturale degli Appenini; la valle del Mugnone, attraverso la quale passa la strada che collega la città a Bologna, crea una spettacolare apertura tra le montagne nell’angolo superiore a sinistra. Fiesole e S. Domenico sono rappresentate con un gruppo di edifici sormontati dal toponimo. Il convento di S. Miniato e di S. Francesco segnano le vette che dominano la città da sud. L’Arno attraversa diagonalmente l’immagine tagliando la città in due parti. Dunque, la rappresentazione del paesaggio non è né evocativo né poetico. Questa rappresentazione senza soluzione di continuità tra la città, fulcro dell’immagine, e il paesaggio, risponde sia alla realtà politica, in quanto i territori rappresentati appartengono di fatto allo Stato fiorentino, sia ad un’ambizione pittorica: sia la città che il paesaggio circostante sono concepiti come uno spazio topografico unitario. La veduta riporta il titolo FIORENZA, variante poetica del toponimo che, come sottolinea David Friedman, fa allusione ai concetti di “fiore” e di “fioritura” e viene usata con intento celebrativo, collegata ai concetti di pace e prosperità” (cfr. Bifolco-Ronca, Cartografia e Topografia Italiana del XVI secolo, pp. 2148-2149)

Etching and engraving, circa 1614, printed on contemporary laid paper with margins, in excellent condition. Rare.

Bibliografia

Bifolco-Ronca, Cartografia e topografia italiana del XVI secolo, pp. 2156-2157, tav. 1099, III/IV; Cartografia Rara (1986): n. 48; Destombes (1970): n. 70; Ganado (1994): VI, n. 107 & p. 212, n. 47; Benevolo (1969): pp. 56-61, tav. VI; Mori-Boffito (1926): pp. 39, 53; Pagani (2012): p. 82; Tooley (1939): n. 206.

|

The name 'Lafreri-School' is a widely used, but rather inaccurate, term used to describe a loose grouping of cartographers, mapmakers, engravers and publishers working in the twin centres of Rome and Venice, from about 1544 to circa 1585. Earlier this century, George Beans, a prominent American collector of Italian maps and atlases, proposed the alternative name 'I.A.T.O.' to describe the composite collections assembled and sold by this school - 'Italian, Assembled-To-Order'. While more apposite, it has failed to catch on with modern cataloguers and collectors. For the purposes of this article, I intend to refer to the cartographers, engravers and publishers involved as "the school", although even this term implies a greater structure and organisation than can currently be established. The principal reference source on the work of the school is R.V. Tooley's Maps in Italian Atlases of the Sixteenth Century (1). In his study, published in 1939, Tooley listed some 614 maps and plates (with variant states counted separately). Some were described from personal examination, others noted from secondary sources and listings. While now much out-dated, as more recent regional carto-bibliographies have effectively superceded particular sections, and new collections have come to light, it remains the only overview of the output of the school. The principal cartographer of the school was Giacomo Gastaldi (fl. 1542-1565), a Piedmontese who worked in Venice, becoming Cosmographer to the Venetian Republic. Karrow described him as "one of the most important cartographers of the sixteenth century. He was certainly the greatest Italian mapmaker of his age..." (2). While his achievement is obvious, it is hard to quantify. A large number of maps were published throughout this period with the geography credited to Gastaldi, but it is often difficult to know what role Gastaldi played in their creation. As a practice, he did not sign himself as publisher, although his name may be found in the title, dedication, or text to the reader. Frequently where there is no imprint one may assume that Gastaldi was the publisher. A further clue may be that many of the maps attributable to Gastaldi as publisher seem to have been engraved by Fabius Licinius. In other cases, where publication is credited to another, it is not always certain whether Gastaldi was commissioned by the publisher to compile the map, whether another less-enterprising publisher merely copied his work and attribution, or simply added Gastaldi's name in the title to add authority to the delineation. His name clearly commanded the same sort of respect that the Sanson name had in the last years of the seventeenth century, and as Guillaume de l'Isle's had in the first half of the eighteenth century. Paolo Forlani was a cartographer and engraver who worked in Venice between 1560 and circa 1571. The majority of his output was published under the imprint of other publishers, such as Giovanni Francesco Camocio, Ferrando Bertelli and Bolognini Zaltieri. In a pioneering study, David Woodward (4), by identifying Forlani's engraving style through various stages of development, has attributed a large number of previously unidentified maps to his hand, and provided a clearer picture of some of the publishing arrangements of the period. In the early 1560s Giovanni Francesco Camocio published a number of maps that were drawn by Forlani, including maps of the World, North Atlantic, Africa, France, Switzerland, and provinces of the Low Countries, to note but a few. Circa 1570, Camocio published an Isolario, or collection of maps of islands, principally from the Mediterranean, but including the British Isles and Iceland. Camocio's earliest issues lacked a title-page, and tended to be a relatively random selection from the available stock. Later he added a title Isole Famose Porti, Fortezze E Terre Maritime. After his death, which is assumed to have been in 1573, the plates were reprinted, with a title-page bearing the Bertelli family address 'alla Libraria del Segno di S. Marco', possibly by Donato Bertelli, whose imprint is found on a later state of Camocio's world map of 1560. The largest grouping was the Bertelli family. The most active was Ferrando Bertelli, who flourished in the 1560's and 1570's, but maps from the last quarter of the seventeenth century are known with the imprints of Andrea, Donato, Lucca, Nicolo and Pietro. Again, a number of maps published by Ferrando were drawn or engraved by Forlani.

Antonio Salamanca (1500 – 1562) settled in Rome his chalcographical business; his activity was then carried on and enlarged by his scholar Antonio Lafrery (1512 – 1577), and then by his grand son Claudio Duchet (Duchetti), Giovanni Orlandi, Henrik van Schoel, and finally by De Rossi. In Venice, the most important centre of map production, he was initiated into engraving by Giovanni Andrea Vavassore and Matteo Pagano, who had worked with Giacomo Gastaldi, the most important European cartographer of the XVI century. Other important exponents of the Venetian chalcography were Fabio Licinio, Fernando Bertelli, Giovanni Francesco Camocio and above all of them Paolo Forlani. Although he’s better known as publisher of Roman archeology, Antoine de Lafrery, born in France, has been the publisher thathas given the biggest impulse to Roman chalcography, becoming in a few years an expert seller as well. For that reason, even though he’s not the one that has published most maps in his time, all the chalcographic works printed in Rome and Venice during the XVI century are nowadays defined as “charts of lafrerian school”. This definition was given by Adolf Erik Nordenskiold, one of the fathers of the history of cartography, who also introduced the definition of Lafrery Atlas, talking about charts printed in Rome and published by Lafrery, in which we find a sort of title page with the title Tavole moderne de geografia secondo l’ordine di Tolomeo. Lafrery’s school produced a huge amount of maps, usually selling them as separate charts and somehow and then edited in a bigger volume. Since the charts had all different measures, the artists needed to trim them with copper to get them to the same size, adding at the end estra pieces of paper, if necessary.

|

|

The name 'Lafreri-School' is a widely used, but rather inaccurate, term used to describe a loose grouping of cartographers, mapmakers, engravers and publishers working in the twin centres of Rome and Venice, from about 1544 to circa 1585. Earlier this century, George Beans, a prominent American collector of Italian maps and atlases, proposed the alternative name 'I.A.T.O.' to describe the composite collections assembled and sold by this school - 'Italian, Assembled-To-Order'. While more apposite, it has failed to catch on with modern cataloguers and collectors. For the purposes of this article, I intend to refer to the cartographers, engravers and publishers involved as "the school", although even this term implies a greater structure and organisation than can currently be established. The principal reference source on the work of the school is R.V. Tooley's Maps in Italian Atlases of the Sixteenth Century (1). In his study, published in 1939, Tooley listed some 614 maps and plates (with variant states counted separately). Some were described from personal examination, others noted from secondary sources and listings. While now much out-dated, as more recent regional carto-bibliographies have effectively superceded particular sections, and new collections have come to light, it remains the only overview of the output of the school. The principal cartographer of the school was Giacomo Gastaldi (fl. 1542-1565), a Piedmontese who worked in Venice, becoming Cosmographer to the Venetian Republic. Karrow described him as "one of the most important cartographers of the sixteenth century. He was certainly the greatest Italian mapmaker of his age..." (2). While his achievement is obvious, it is hard to quantify. A large number of maps were published throughout this period with the geography credited to Gastaldi, but it is often difficult to know what role Gastaldi played in their creation. As a practice, he did not sign himself as publisher, although his name may be found in the title, dedication, or text to the reader. Frequently where there is no imprint one may assume that Gastaldi was the publisher. A further clue may be that many of the maps attributable to Gastaldi as publisher seem to have been engraved by Fabius Licinius. In other cases, where publication is credited to another, it is not always certain whether Gastaldi was commissioned by the publisher to compile the map, whether another less-enterprising publisher merely copied his work and attribution, or simply added Gastaldi's name in the title to add authority to the delineation. His name clearly commanded the same sort of respect that the Sanson name had in the last years of the seventeenth century, and as Guillaume de l'Isle's had in the first half of the eighteenth century. Paolo Forlani was a cartographer and engraver who worked in Venice between 1560 and circa 1571. The majority of his output was published under the imprint of other publishers, such as Giovanni Francesco Camocio, Ferrando Bertelli and Bolognini Zaltieri. In a pioneering study, David Woodward (4), by identifying Forlani's engraving style through various stages of development, has attributed a large number of previously unidentified maps to his hand, and provided a clearer picture of some of the publishing arrangements of the period. In the early 1560s Giovanni Francesco Camocio published a number of maps that were drawn by Forlani, including maps of the World, North Atlantic, Africa, France, Switzerland, and provinces of the Low Countries, to note but a few. Circa 1570, Camocio published an Isolario, or collection of maps of islands, principally from the Mediterranean, but including the British Isles and Iceland. Camocio's earliest issues lacked a title-page, and tended to be a relatively random selection from the available stock. Later he added a title Isole Famose Porti, Fortezze E Terre Maritime. After his death, which is assumed to have been in 1573, the plates were reprinted, with a title-page bearing the Bertelli family address 'alla Libraria del Segno di S. Marco', possibly by Donato Bertelli, whose imprint is found on a later state of Camocio's world map of 1560. The largest grouping was the Bertelli family. The most active was Ferrando Bertelli, who flourished in the 1560's and 1570's, but maps from the last quarter of the seventeenth century are known with the imprints of Andrea, Donato, Lucca, Nicolo and Pietro. Again, a number of maps published by Ferrando were drawn or engraved by Forlani.

Antonio Salamanca (1500 – 1562) settled in Rome his chalcographical business; his activity was then carried on and enlarged by his scholar Antonio Lafrery (1512 – 1577), and then by his grand son Claudio Duchet (Duchetti), Giovanni Orlandi, Henrik van Schoel, and finally by De Rossi. In Venice, the most important centre of map production, he was initiated into engraving by Giovanni Andrea Vavassore and Matteo Pagano, who had worked with Giacomo Gastaldi, the most important European cartographer of the XVI century. Other important exponents of the Venetian chalcography were Fabio Licinio, Fernando Bertelli, Giovanni Francesco Camocio and above all of them Paolo Forlani. Although he’s better known as publisher of Roman archeology, Antoine de Lafrery, born in France, has been the publisher thathas given the biggest impulse to Roman chalcography, becoming in a few years an expert seller as well. For that reason, even though he’s not the one that has published most maps in his time, all the chalcographic works printed in Rome and Venice during the XVI century are nowadays defined as “charts of lafrerian school”. This definition was given by Adolf Erik Nordenskiold, one of the fathers of the history of cartography, who also introduced the definition of Lafrery Atlas, talking about charts printed in Rome and published by Lafrery, in which we find a sort of title page with the title Tavole moderne de geografia secondo l’ordine di Tolomeo. Lafrery’s school produced a huge amount of maps, usually selling them as separate charts and somehow and then edited in a bigger volume. Since the charts had all different measures, the artists needed to trim them with copper to get them to the same size, adding at the end estra pieces of paper, if necessary.

|