| Reference: | S49965 |

| Author | Giovan Battista PIRANESI |

| Year: | 1768 |

| Printed: | Rome |

| Measures: | 650 x 410 mm |

| Reference: | S49965 |

| Author | Giovan Battista PIRANESI |

| Year: | 1768 |

| Printed: | Rome |

| Measures: | 650 x 410 mm |

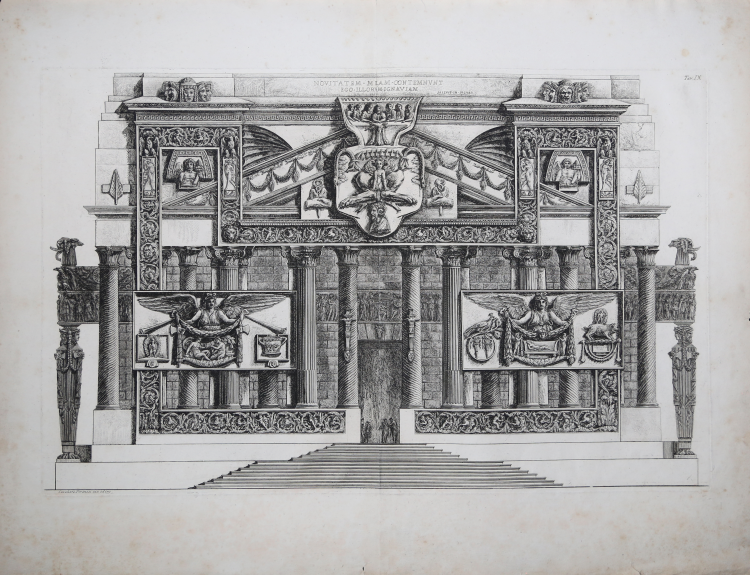

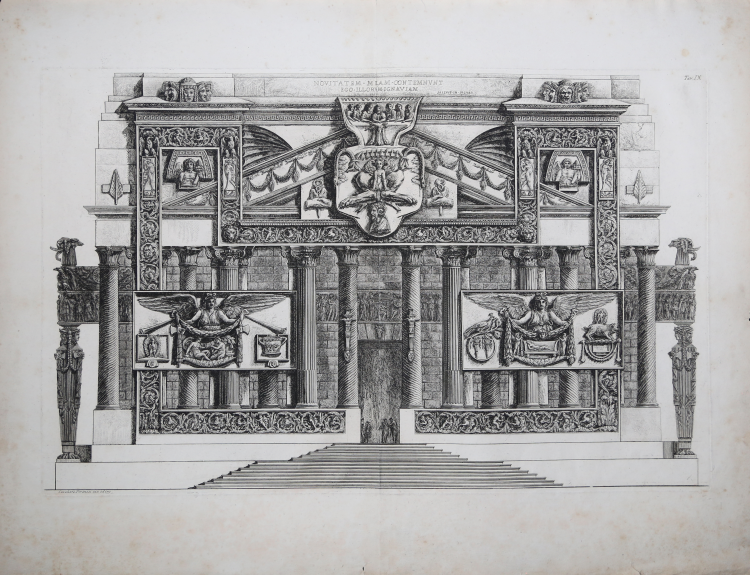

Etching, 1768 circa, signed on plate at lower left Cavaliere Piranesi inv. ed inc.

From Osservazioni di Gio. Battista Piranesi sopra la lettre de M. Mariette aux auteurs de la Gazette Littéraire de l'Europe, Inserita nel Supplemento dell'istessa Gazzetta stampata Dimanche 4 Novembre MDCCLIV. Parere su l'Architettura, con una Prefazione ad un nuovo Trattato della introduzione e del progresso delle belle arti in Europa ne' tempi antichi [Observations of Giovanni Battista Piranesi on the letter of M. Mariette to the authors of the Gazette Littéraire de l'Europe, included in the Supplement of the same Gazette printed Sunday, 4 November 1754 [1764]. And opinions on Architecture, together with a Preface to a new Treatise on the introduction and the progress of the Fine Arts in Europe in ancient times] printed in Rome, 1765.

Towards the mid-1760s Piranesi's involvement in the academic exchanges of the Graeco-Roman debate was overtaken by a developing concern with evolving an imaginative system of modern design, drawing freely on all forms of ancient art. With the active encouragement of Pope Clement XIII and other members of the Rezzonico family, these novel ideas were given practical expression in commissions for architecture, furniture and interior decoration. Piranesi, preferring the creative license of the artist to the restrictive theories of rigorists like Laugier and Winkelmann, re-entered the debate in 1765 with a work which was to be as much an artistic manifesto as a polemical riposte. In 1764 the French critic Mariette had attacked Piranesi's theories as expressed in Della Magnificenza with an article in the Gazette Littéraire de l'Europe. Rejecting the claims of the Etruscans' originality on the grounds that they had been Greek colonists, Mariette considered that all Roman art derived from that of Greece; having been carried out in Rome by Greek slaves, it underwent a decline. The French critic, echoing the increasingly dominant views of Winckelmann in the debate, asserted that the Greek style dis- played "une belle et noble simplicité." Piranesi's rejoinder was a 1765 publication involving three separate elements. In the Osservazioni... sopra la lettre de M. Mariette he repeated the principal arguments of Della Magnificenza, refuting Mariette virtually sentence by sentence. The title page of the former publication, however, represents the more complex situation that Piranesi had reached intellectually during the intervening years. Although this plate is dominated by the Tuscan Order, as an invention of the Etruscans and independent of the Greek Doric, the main issue for Piranesi artistic originality was more profound, as two insets make clear. In the upper one Mariette's left hand is shown writing his letter together with the words aut cum hoc while below, in the profile of the column, appear the tools of the artist accompanied by the words aut in hoc. The point thus made is that such discussions of art are beyond the experience of armchair critics like Mariette, and can only be resolved by active designers who, like Piranesi, are in far closer contact with the creative spirit of antiquity.

The second element of this publication, the Parere su l'Architettura, is undoubtedly one of his most significant works, particularly as it establishes for the first time a theoretical basis for his artistic inclinations towards complexity rather than Attic simplicity. It takes the form of a Socratic dialogue between two architects. Protopiro represents the "progressive" school of designers, committed to Laugier's functionalist theories and to Winckelmann's ideals of Greek austerity. Didascalo voices Piranesi's criticism of the sterile limitations of such attitudes and argues in favor of creative license.

The text of the Parere was originally illustrated by only a couple of vignettes, which show novel forms of architectural composition in which Etruscan and Roman motifs are combined and in which all the rules of Vitruvian and Palladian design are broken with a neo-Mannerist taste for reversing conventional elements. This approach, however, was dramatically developed and much exaggerated for polemical effect in five further plates, added to the Parere at some point after 1768, given that Piranesi was able to inscribe himself Calvaliere on them. (Pope Clement XIII conferred the Order of the Sperone d'Oro on Piranesi in October, 1766, but it was only after the relevant papal brief was issued on 16 January, 1767 that he was able to use the title.) In these later plates the last traces of conventional forms have disappeared and Greek as well as Egyptian motifs are now crowded together with Etruscan and Roman ornament. Various quotations from the Latin authors affirm the need for such a radical approach if architecture is to progress; anticipating his critics Piranesi quotes Sallust: Novitatem meam contemnunt, ego illorum ignaviam (They despise my novelty, I their timidity). Although the final element of the publication of 1765 was ambitiously entitled Trattato della introduzione e del progresso delle belle arti in Europa ne' tempi antichi, in it Piranesi merely restates his thesis on the originality of Italy over Greece. By way of illustration he adds three plates depicting the extensive variety of patterns invented by the Etruscans for their tombs at Chiusi and Corneto.

Magnificent example, printed on contemporary laid paper, light foxing, otherwise in excellent condition.

Bibliografia

H. Focillon, Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1918), n. 982; Wilton-Ely n. 814.

Giovan Battista PIRANESI (Mogliano Veneto 1720 - Roma 1778)

|

Italian etcher, engraver, designer, architect, archaeologist and theorist. He is considered one of the supreme exponents of topographical engraving, but his lifelong preoccupation with architecture was fundamental to his art. Although few of his architectural designs were executed, he had a seminal influence on European Neo-classicism through personal contacts with architects, patrons and visiting artists in Rome over the course of nearly four decades. His prolific output of etched plates, which combined remarkable flights of imagination with a strongly practical understanding of ancient Roman technology, fostered a new and lasting perception of antiquity. He was also a designer of festival structures and stage sets, interior decoration and furniture, as well as a restorer of antiquities. The interaction of this rare combination of activities led him to highly original concepts of design, which were advocated in a body of influential theoretical writings. The ultimate legacy of his unique vision of Roman civilization was an imaginative interpretation and re-creation of the past, which inspired writers and poets as much as artists and designers.

|

Giovan Battista PIRANESI (Mogliano Veneto 1720 - Roma 1778)

|

Italian etcher, engraver, designer, architect, archaeologist and theorist. He is considered one of the supreme exponents of topographical engraving, but his lifelong preoccupation with architecture was fundamental to his art. Although few of his architectural designs were executed, he had a seminal influence on European Neo-classicism through personal contacts with architects, patrons and visiting artists in Rome over the course of nearly four decades. His prolific output of etched plates, which combined remarkable flights of imagination with a strongly practical understanding of ancient Roman technology, fostered a new and lasting perception of antiquity. He was also a designer of festival structures and stage sets, interior decoration and furniture, as well as a restorer of antiquities. The interaction of this rare combination of activities led him to highly original concepts of design, which were advocated in a body of influential theoretical writings. The ultimate legacy of his unique vision of Roman civilization was an imaginative interpretation and re-creation of the past, which inspired writers and poets as much as artists and designers.

|