| Reference: | S45117 |

| Author | Etienne DUPERAC |

| Year: | 1569 |

| Zone: | San Pietro |

| Measures: | 410 x 475 mm |

| Reference: | S45117 |

| Author | Etienne DUPERAC |

| Year: | 1569 |

| Zone: | San Pietro |

| Measures: | 410 x 475 mm |

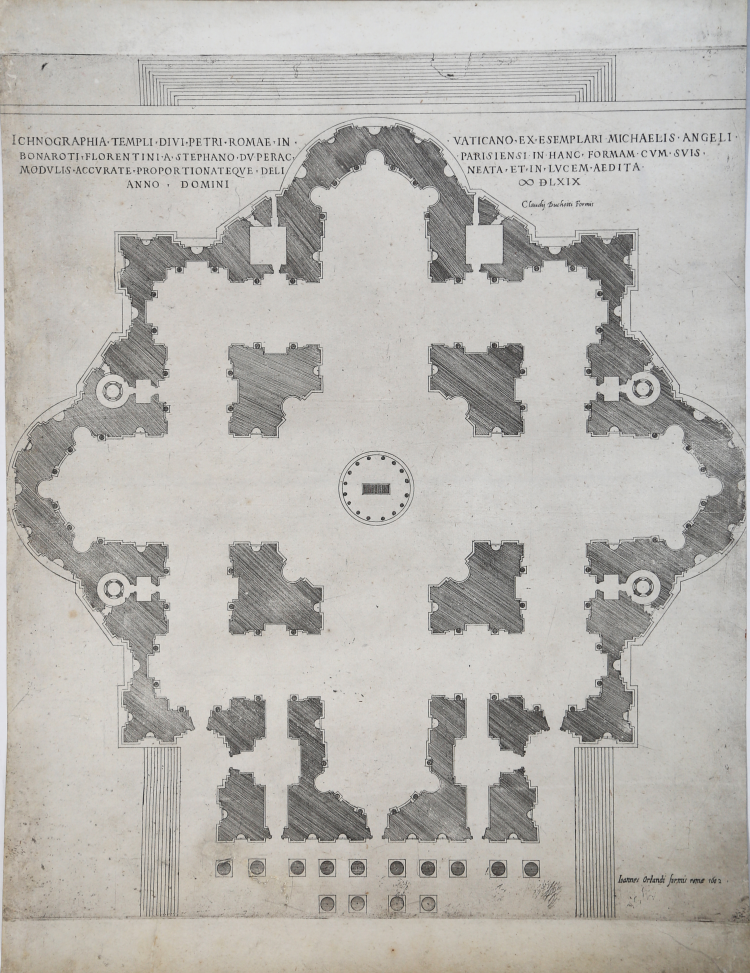

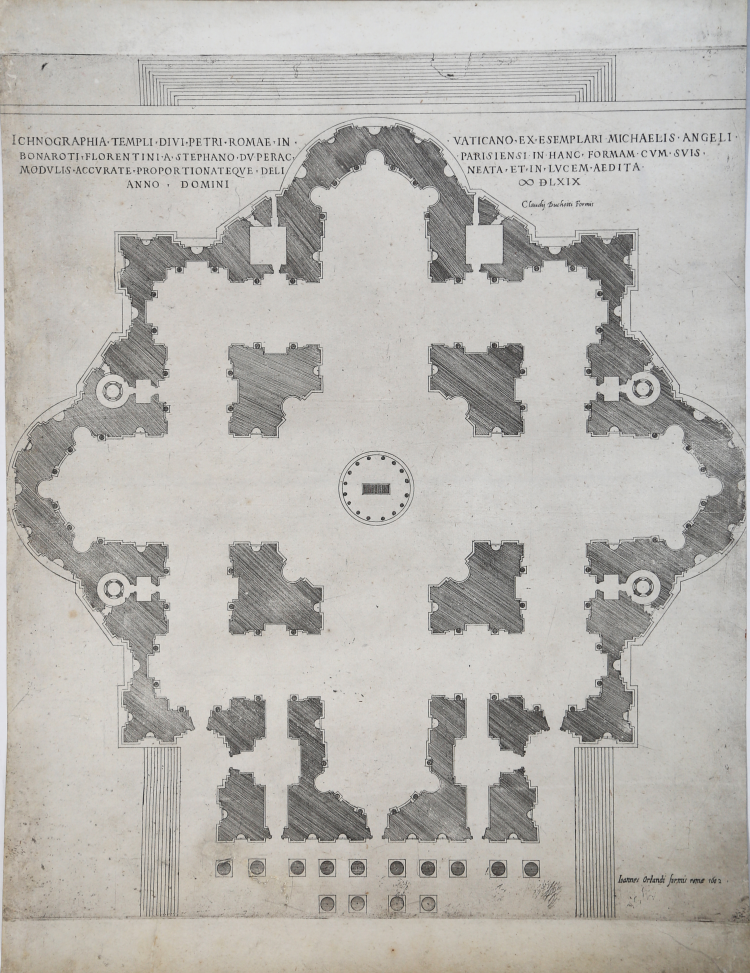

Etching, 1569, titled, signed and dated at top: ICHNOGRAPHIA TEMPLI DIVI PETRI ROMAE IN VATICANO EX ESEMPLARI MICHAELIS ANGELI BONAROTI FLORENTINI A STEPHANO DV PERAC PARISIENSI IN HANC FORMAM CVM SVIS MODVLIS ACCVRATE PROPORTIONATEQVE DELINEATA ET IN LVCEM AEDITA ANNO DOMINI ∞ DLXIX [Icnography of the Temple of St. Peter, at Rome, in the Vatican from the example of Michelangelo Buonarroti, Florentine, accurately and proportionately delineated in this form and with its forms by Stephen du Perac of Paris, and edited in the year 1569].

Example in the third state of four, with the imprint of Giovanni Orlandi: Ioannes Orlandi formis romae 1602.

Beautiful proof, richly toned, printed on laid paper, irregularly trimmed to copperplate (inside about 5 mm on right side), margins top and bottom, in good condition. Laid down antique cardbord.

“The plan, drawn by Étienne Du Pérac in 1569, is the first of three made most likely between 1569 and 1570 and lacks the publisher's address. The drawing was generally believed to be an expression of Michelangelo's intentions for the plan of St. Peter's. Du Pérac, however, in all likelihood knew little of Michelangelo's real plan, so according to Anna Bedon, "of St. Peter's he reports what he sees built, what he sees of the model, what he learns from Ligorio who had recently left the position of 'architect of St. Peter's,' so he cross-references his sources but, unlike Faleti and Luchino, invents what is still missing or not visible to him." After all, "the order to follow the new St. Peter's with permission to change what had already been done (at least within certain limits) meant first of all to reduce the vain triumphalism of the sumptuous and complicated Sangallesque project, then to make true doctrine visible in architectural form, and finally to make the church a mighty weapon against heresy. It is well known that Michelangelo made a scruple of that task, to the point of obsession: on the outcome of the immense task would depend the salvation of his soul. And he was old, death was near" (G. C. Argan). The various interpretations arising from Du Pérac's series of three prints raise more questions than plausible explanations as Federico Bellini reports "This group of three engravings constitutes one of the major problems in sixteenth-century historiography. It is likely that Dupérac's prints represent what the Frenchman had managed to learn about the project carried out by Vignola in March 1567, that is, when the building site resumed with the foundations of the chapel of San Michele. Only the plan is dated to 1569, but it is almost certain that the cutaway and the view are perfectly contemporary with it: this is deduced from the scale of reduction, which barring a negligible measure is the same in the three graphs; and from the characters of the epigraphs, which are likewise the same” (translation from C. Marigliani, Lo splendore di Roma nell’Arte incisoria del Cinquecento).

The work belongs to the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, the earliest iconography of ancient Rome.

The Speculum originated in the publishing activities of Antonio Salamanca and Antonio Lafreri (Lafrery). During their Roman publishing careers, the two editors-who worked together between 1553 and 1563-started the production of prints of architecture, statuary, and city views related to ancient and modern Rome. The prints could be purchased individually by tourists and collectors, but they were also purchased in larger groups that were often bound together in an album. In 1573, Lafreri commissioned a frontispiece for this purpose, where the title Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae appears for the first time. Upon Lafreri's death, two-thirds of the existing copperplates went to the Duchetti family (Claudio and Stefano), while another third was distributed among several publishers. Claudio Duchetti continued the publishing activity, implementing the Speculum plates with copies of those "lost" in the hereditary division, which he had engraved by the Milanese Amborgio Brambilla. Upon Claudio's death (1585) the plates were sold - after a brief period of publication by the heirs, particularly in the figure of Giacomo Gherardi - to Giovanni Orlandi, who in 1614 sold his printing house to the Flemish publisher Hendrick van Schoel. Stefano Duchetti, on the other hand, sold his own plates to the publisher Paolo Graziani, who partnered with Pietro de Nobili; the stock flowed into the De Rossi typography passing through the hands of publishers such as Marcello Clodio, Claudio Arbotti and Giovan Battista de Cavalleris. The remaining third of plates in the Lafreri division was divided and split among different publishers, some of them French: curious to see how some plates were reprinted in Paris by Francois Jollain in the mid-17th century. Different way had some plates printed by Antonio Salamanca in his early period; through his son Francesco, they goes to Nicolas van Aelst's. Other editors who contributed to the Speculum were the brothers Michele and Francesco Tramezzino (authors of numerous plates that flowed in part to the Lafreri printing house), Tommaso Barlacchi, and Mario Cartaro, who was the executor of Lafreri's will, and printed some derivative plates. All the best engravers of the time - such as Nicola Beatrizet (Beatricetto), Enea Vico, Etienne Duperac, Ambrogio Brambilla, and others - were called to Rome and employed for the intaglio of the works.

All these publishers-engravers and merchants-the proliferation of intaglio workshops and artisans helped to create the myth of the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, the oldest and most important iconography of Rome. The first scholar to attempt to systematically analyze the print production of 16th-century Roman printers was Christian Hülsen, with his Das Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae des Antonio Lafreri of 1921. In more recent times, very important have been the studies of Peter Parshall (2006) Alessia Alberti (2010), Birte Rubach and Clemente Marigliani (2016).

Bibliografia

C. Hülsen, Das Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae des Antonio Lafreri (1921), n. 95; cfr. Peter Parshall, Antonio Lafreri's 'Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, in “Print Quarterly”, 1 (2006); B. Rubach, Ant. Lafreri Formis Romae (2016), n. 368, III/IV; A. Alberti, L’indice di Antonio Lafrery (2010), n. A. 147, III/IV; Marigliani, Lo splendore di Roma nell’Arte incisoria del Cinquecento (2016), n. VIII.13; cfr. D. Woodward, Catalogue of watermarks in Italian printed maps 1540 – 1600 (1996).

|

Etcher, engraver, painter and architect, from Bordeaux. Active in Venice and from 1559 in Rome.Returned to France either in 1578 or 1582. Died in Paris.

Duperac worked for various Roman print dealers, including Lafreri, Vaccari ,Faleti and P.P. Palumbo.He himself published some of his own work.Specialized in antiquities,maps and views.

Urbis Romae sciographia ex antiquis monumentis accuratiss. Delineata,1574.

Also the series,Vestigi dell’antichità di Roma ,1575.

|

|

Etcher, engraver, painter and architect, from Bordeaux. Active in Venice and from 1559 in Rome.Returned to France either in 1578 or 1582. Died in Paris.

Duperac worked for various Roman print dealers, including Lafreri, Vaccari ,Faleti and P.P. Palumbo.He himself published some of his own work.Specialized in antiquities,maps and views.

Urbis Romae sciographia ex antiquis monumentis accuratiss. Delineata,1574.

Also the series,Vestigi dell’antichità di Roma ,1575.

|