| Reference: | S45972 |

| Author | Jean Baptiste NOLIN II |

| Year: | 1817 |

| Zone: | The World |

| Printed: | Paris |

| Measures: | 645 x 485 mm |

| Reference: | S45972 |

| Author | Jean Baptiste NOLIN II |

| Year: | 1817 |

| Zone: | The World |

| Printed: | Paris |

| Measures: | 645 x 485 mm |

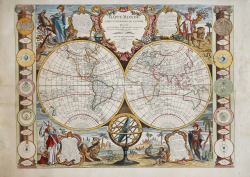

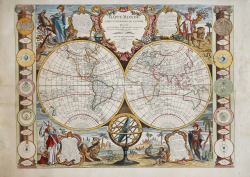

Mappe-Monde Carte Universelle de la Terre Dressee Sur les Relations les plus Nouvelles Soumises aux Observations Astronomique les plus recentes ou sont marquees les Nouvelles Decouvertes . . . 1817.

Uncommon and highly decorative map of the world in two hemispheres. First published in 1755, this edition has been updated based on new discoveries in the Pacific, with significantly updated information for Austalia, New Zealand, and the northwest coast of America, incorporating the voyages of La Perouse, Vancouver, and others. Australia and New Zealand reflect updated coastlines, although the shape of the two New Zealand islands is rather odd. The map has been published for more than 50 years, with regular revisions to the cartographic content.

First printed by Jean Baptiste Nolin II (1686-1762), it was revised and updated by Louis Denis (d. 1794) and André Basset (d. 1787). The latest reprints, further updated, are published by his son Paul-André Basset. Different editions of 1759, 1777, 1782, 1792, 1796, 1808, 1811 and 1817 are known.

In the North Pacific, the coastlines of North America have been improved and Alaska is taking shape. Changes have also been made to the islands northeast of Honshu, but these do not improve the accuracy of the depiction of Hokkaido, and several provisional islands still remain, including Terre de la Compagnie (Land of the Company). In the South Pacific, Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand are now fully delineated, although the coastlines are still rudimentary. The tracks of numerous explorers fill the oceans, including Cook, Byron, Bougainville and Furneaux.

In the interior of North America there are only a few place names, including Quebec, Boston, Philadelphia, Charleston, St. Augustine, and New Orleans. Although a few changes have been made to North America since the 1755 edition, such as the inclusion of the United States east of the Mississippi and Louisiana to the west, the British colonies (Colonies Angloises) are still listed along the east coast. In addition, Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron are still connected. Although the West Sea no longer appears, a possible Northwest Passage connects Hudson Bay to the Arctic Ocean north of Canada.

At the corners of the map there are splendid vignettes representing the four continents, each with an allegorical figure presenting a cartouche containing descriptive text, accompanied by a native animal and set in an exotic landscape. Europe includes a horse and symbols of the arts, sciences and war. Africa wears an elephant's head as a hat and stands next to a lion, while Asia holds incense next to a camel. America wears a feathered costume and holds a bow, while a large dinosaur-like creature lies next to an oddly shaped human who appears to be eating a round fruit. The sides of the map are lined with columns showing 10 astronomical diagrams of the sun, moon, and planetary systems. An armillary sphere is found in the lower cusp of the map, while a grandly decorative titled cartouche is found in the upper cusp.

Louis Denis (1725-1794) was a French engraver, cartographer and geographer. He is best known for having published Le Conducteur français, a guide on the streets of the kingdom of France. We know very little about his life; it seems that his original occupation was that of an engraver. In 1760, he joined forces with engineer-geographer and publisher Louis-Charles Desnos to modify and update existing maps. Louis Denis had the title of "géographe des enfants de France"; gave the Duke of Berry, future Louis XVI, a solid geographical culture. His most important work was Le Conducteur français, contained in the routes desservies par les nouvelles diligences, messageries & autres voitures publiques; avec un détail historique & topographique des endroits où elles passent, même de ceux qu'on peut apercevoir [sic]; des notes curieuses sur les chaînes des montagnes qu'on rencontre, etc. : these are travel itineraries for each of the main streets of the kingdom, accompanied by maps of high precision and quality that make it one of the ancestors of modern travel guides. Begun in 1776, the work was never completed; only 52 travel itineraries were published. Each booklet obtained the approval of Didier Robert de Vaugondy (1723-1786) who from 1773 was royal censor for geography, navigation and travel. Louis Denis was also the author of numerous plans in Paris, printed between 1758 and 1781.

Andrè Basset "the young" was a publisher, writer and print dealer. Brothers of the bookseller and print publisher Antoine Basset "the old". He had a shop on Rue St. Jacques, the Parisian street of engravers and printers, and he printed with the typographical mark with "Image S.te Genevieve". Died in June 1787, he is often confused with his son and successor Paul-André Basset.

Etching with magnificent hand colouring, minimal restored tears, otherwise in excellent condition. Rare.

Bibliografia

Cfr. Tooley, Mapmakers I, 358 (Louis Denis, 1725-1794: "Aggiornate diverse mappe da Nolin... ripubblicate da Basset, 1793"; cfr. McGuirk #49.

Jean Baptiste NOLIN II (1686 - 1762)

|

Jean-Baptiste Nolin (ca. 1657-1708) was a French engraver who worked at the turn of the eighteenth century. Initially trained by Francois de Poilly, his artistic skills caught the eye of Vincenzo Coronelli when the latter was working in France. Coronelli encouraged the young Nolin to engrave his own maps, which he began to do.

Whereas Nolin was a skilled engraver, he was not an original geographer. He also had a flair for business, adopting monikers like the Geographer to the Duke of Orelans and Engerver to King XIV. He, like many of his contemporaries, borrowed liberally from existing maps. In Nolin’s case, he depended especially on the works of Coronelli and Jean-Nicholas de Tralage, the Sieur de Tillemon. This practice eventually caught Nolin in one of the largest geography scandals of the eighteenth century.

In 1700, Nolin published a large world map which was seen by Claude Delisle, father of the premier mapmaker of his age, Guillaume Delisle. Claude recognized Nolin’s map as being based in part on his son’s work. Guillaume had been working on a manuscript globe for Louis Boucherat, the chancellor of France, with exclusive information about the shape of California and the mouth of the Mississippi River. This information was printed on Nolin’s map. The court ruled in the Delisles’ favor after six years. Nolin had to stop producing that map, but he continued to make others.

Calling Nolin a plagiarist is unfair, as he was engaged in a practice that practically every geographer adopted at the time. Sources were few and copyright laws weak or nonexistent. Nolin’s maps are engraved with considerable skill and are aesthetically engaging.

Nolin’s son, also Jean-Baptiste (1686-1762), continued his father’s business.

|

Jean Baptiste NOLIN II (1686 - 1762)

|

Jean-Baptiste Nolin (ca. 1657-1708) was a French engraver who worked at the turn of the eighteenth century. Initially trained by Francois de Poilly, his artistic skills caught the eye of Vincenzo Coronelli when the latter was working in France. Coronelli encouraged the young Nolin to engrave his own maps, which he began to do.

Whereas Nolin was a skilled engraver, he was not an original geographer. He also had a flair for business, adopting monikers like the Geographer to the Duke of Orelans and Engerver to King XIV. He, like many of his contemporaries, borrowed liberally from existing maps. In Nolin’s case, he depended especially on the works of Coronelli and Jean-Nicholas de Tralage, the Sieur de Tillemon. This practice eventually caught Nolin in one of the largest geography scandals of the eighteenth century.

In 1700, Nolin published a large world map which was seen by Claude Delisle, father of the premier mapmaker of his age, Guillaume Delisle. Claude recognized Nolin’s map as being based in part on his son’s work. Guillaume had been working on a manuscript globe for Louis Boucherat, the chancellor of France, with exclusive information about the shape of California and the mouth of the Mississippi River. This information was printed on Nolin’s map. The court ruled in the Delisles’ favor after six years. Nolin had to stop producing that map, but he continued to make others.

Calling Nolin a plagiarist is unfair, as he was engaged in a practice that practically every geographer adopted at the time. Sources were few and copyright laws weak or nonexistent. Nolin’s maps are engraved with considerable skill and are aesthetically engaging.

Nolin’s son, also Jean-Baptiste (1686-1762), continued his father’s business.

|