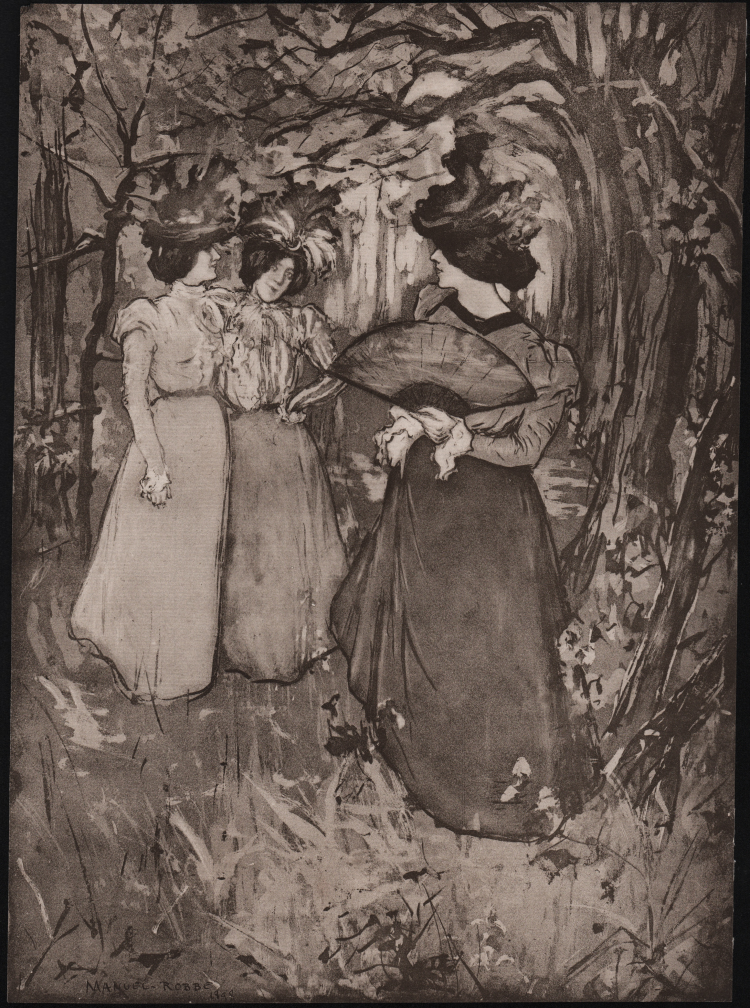

| Reference: | S42131 |

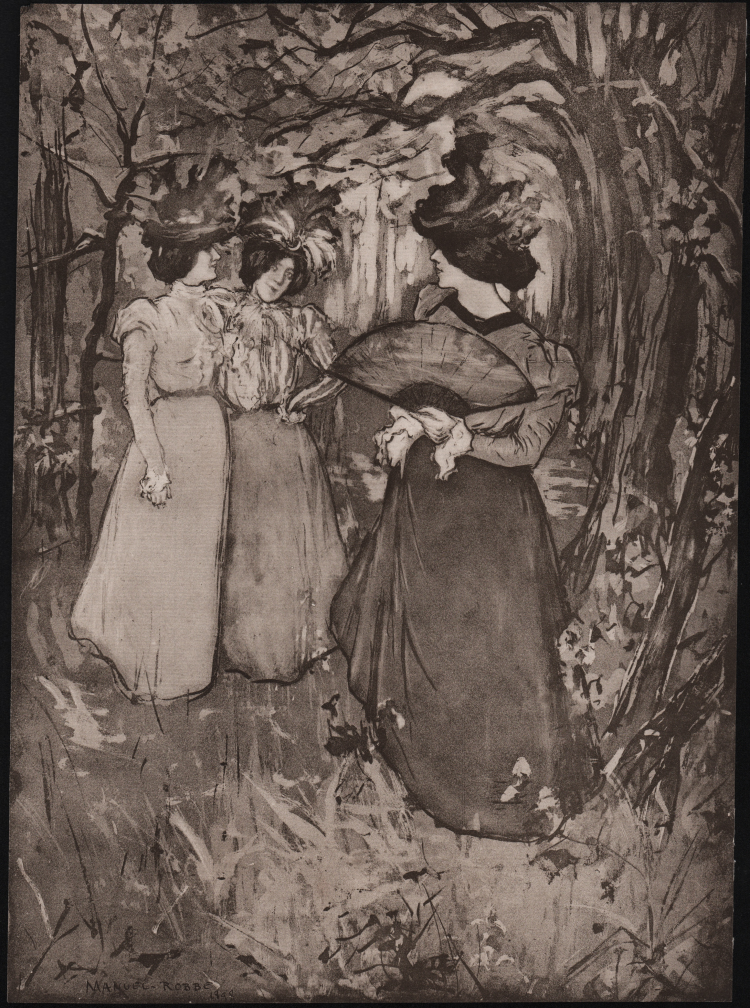

| Author | Manuel ROBBE |

| Year: | 1898 |

| Measures: | 240 x 330 mm |

| Reference: | S42131 |

| Author | Manuel ROBBE |

| Year: | 1898 |

| Measures: | 240 x 330 mm |

Colour lithograph, signed in plate, lower left corner of image ‘MANUEL ROBBE/ 1898’. Excellent condition.

From L’Estampe Moderne vol. 2, no. 16, August 1898; printed by L’Imprimerie Champenois, distributed by Masson & Pizza.

Manuel Robbe (1872-1936), born in Paris, he was descended from a northern French family from the town of Berthune. He studied painting and etching, and soon became an accomplished engraver, specializing in the medium of aquatint. He exhibited regularly at the Salons of the Societé des Artistes Français. Edmond Sagot, one of the most significant publishers of prints at the turn of the 20th century, was a great admirer of Manuel Robbe, and regularly published color prints by him.

Between then and the outbreak of the war in 1914, Robbe executed a large number of aquatints in color and in black. In 1900 Manuel Robbe was awarded a Gold Medal at the Universal Exhibition for his prints. In 1905 he transferred his allegiance from the Societé des Artistes Français to the Societé Nationale des Beaux-Arts, in whose annual salons he was henceforth to exhibit. In 1902-03, the prestigious art critic Gabriel Moury, writing for the English based The Studio, noted that “Robbe especially excels in depicting the modern woman. A somewhat Special type of modern woman.” Moury was sensitive to Robbe’s wide range of feminine types acknowledging that some of Robbe’s prints either focused on “the lady, the artist’s wife or the model—seated or reclining or standing, in a studio or a drawing room, or studying some work of art.”

Robbe’s personal vision is found in his visualization of the women of Paris during the intriguing era of the Belle Epoque. His personal views are even more powerful, as Robbe was a great technician in drypoint and in color aquatint, inventing a technique known as “sugar-lift” which gave his prints a startling subtlety. Robbe’s technique was developed over several phases. He printed his design with a mixture of sugar, India ink and gum Arabic, on his zinc plate. This was followed by heating the plate and working with the soft-ground etching process until the desired result was achieved. Finally, Robbe painted the subject on the zinc plate with an oil paint brush. For this process he used a special brush made of rags, which was called “a la poupée “ (with a doll). This process was used by French engravers of the 18th century. In completing his image, Robbe used his fingers to play with the tone on the zinc plate, whereby many of this color prints appear completely unique. He arrived at new shades of color every time he pulled an impression; for example, park scenes appear in spring colors and also in colors associated with autumn.

The influences on Robbe were varied. Renoir’s influence is apparent in his upper middle class women of the Belle Epoque, especially in scenes of women in their boudoirs, with children in the parks, and playing the piano, in the promenades and the streets where the essence of happiness is expressed.

References:

Weisberg, Gabriel. Manuel Robbe: From Impressionism to Symbolism, 19.

|

Manuel Robbe, born in Paris, was descended from a northern French family from the town of Berthune. He studied painting and etching, and soon became an accomplished engraver, specializing in the medium of aquatint. He exhibited regularly at the Salons of the Societé des Artistes Français. Edmond Sagot, one of the most significant publishers of prints at the turn of the 20th century, was a great admirer of Manuel Robbe, and regularly published color prints by him.

Between then and the outbreak of the war in 1914, Robbe executed a large number of aquatints in color and in black. In 1900 Manuel Robbe was awarded a Gold Medal at the Universal Exhibition for his prints. In 1905 he transferred his allegiance from the Societé des Artistes Français to the Societé Nationale des Beaux-Arts, in whose annual salons he was henceforth to exhibit. In 1902-03, the prestigious art critic Gabriel Moury, writing for the English based The Studio, noted that “Robbe especially excels in depicting the modern woman. A somewhat Special type of modern woman.” Moury was sensitive to Robbe’s wide range of feminine types acknowledging that some of Robbe’s prints either focused on “the lady, the artist’s wife or the model—seated or reclining or standing, in a studio or a drawing room, or studying some work of art.”

Robbe’s personal vision is found in his visualization of the women of Paris during the intriguing era of the Belle Epoque. His personal views are even more powerful, as Robbe was a great technician in drypoint and in color aquatint, inventing a technique known as “sugar-lift” which gave his prints a startling subtlety. Robbe’s technique was developed over several phases. He printed his design with a mixture of sugar, India ink and gum Arabic, on his zinc plate. This was followed by heating the plate and working with the soft-ground etching process until the desired result was achieved. Finally, Robbe painted the subject on the zinc plate with an oil paint brush. For this process he used a special brush made of rags, which was called “a la poupée “ (with a doll). This process was used by French engravers of the 18th century. In completing his image, Robbe used his fingers to play with the tone on the zinc plate, whereby many of this color prints appear completely unique. He arrived at new shades of color every time he pulled an impression; for example, park scenes appear in spring colors and also in colors associated with autumn.

The influences on Robbe were varied. Renoir’s influence is apparent in his upper middle class women of the Belle Epoque, especially in scenes of women in their boudoirs, with children in the parks, and playing the piano, in the promenades and the streets where the essence of happiness is expressed.

|

|

Manuel Robbe, born in Paris, was descended from a northern French family from the town of Berthune. He studied painting and etching, and soon became an accomplished engraver, specializing in the medium of aquatint. He exhibited regularly at the Salons of the Societé des Artistes Français. Edmond Sagot, one of the most significant publishers of prints at the turn of the 20th century, was a great admirer of Manuel Robbe, and regularly published color prints by him.

Between then and the outbreak of the war in 1914, Robbe executed a large number of aquatints in color and in black. In 1900 Manuel Robbe was awarded a Gold Medal at the Universal Exhibition for his prints. In 1905 he transferred his allegiance from the Societé des Artistes Français to the Societé Nationale des Beaux-Arts, in whose annual salons he was henceforth to exhibit. In 1902-03, the prestigious art critic Gabriel Moury, writing for the English based The Studio, noted that “Robbe especially excels in depicting the modern woman. A somewhat Special type of modern woman.” Moury was sensitive to Robbe’s wide range of feminine types acknowledging that some of Robbe’s prints either focused on “the lady, the artist’s wife or the model—seated or reclining or standing, in a studio or a drawing room, or studying some work of art.”

Robbe’s personal vision is found in his visualization of the women of Paris during the intriguing era of the Belle Epoque. His personal views are even more powerful, as Robbe was a great technician in drypoint and in color aquatint, inventing a technique known as “sugar-lift” which gave his prints a startling subtlety. Robbe’s technique was developed over several phases. He printed his design with a mixture of sugar, India ink and gum Arabic, on his zinc plate. This was followed by heating the plate and working with the soft-ground etching process until the desired result was achieved. Finally, Robbe painted the subject on the zinc plate with an oil paint brush. For this process he used a special brush made of rags, which was called “a la poupée “ (with a doll). This process was used by French engravers of the 18th century. In completing his image, Robbe used his fingers to play with the tone on the zinc plate, whereby many of this color prints appear completely unique. He arrived at new shades of color every time he pulled an impression; for example, park scenes appear in spring colors and also in colors associated with autumn.

The influences on Robbe were varied. Renoir’s influence is apparent in his upper middle class women of the Belle Epoque, especially in scenes of women in their boudoirs, with children in the parks, and playing the piano, in the promenades and the streets where the essence of happiness is expressed.

|