| Reference: | S44743 |

| Author | Georg GROSZ |

| Year: | 1922 ca. |

| Measures: | 250 x 345 mm |

| Reference: | S44743 |

| Author | Georg GROSZ |

| Year: | 1922 ca. |

| Measures: | 250 x 345 mm |

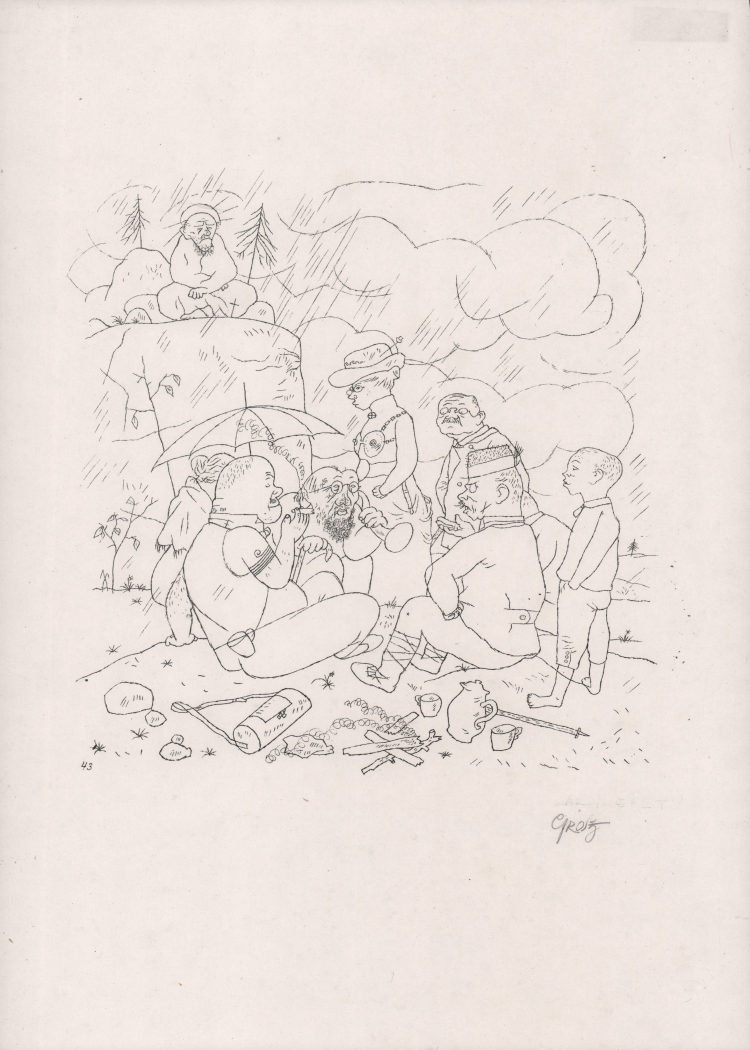

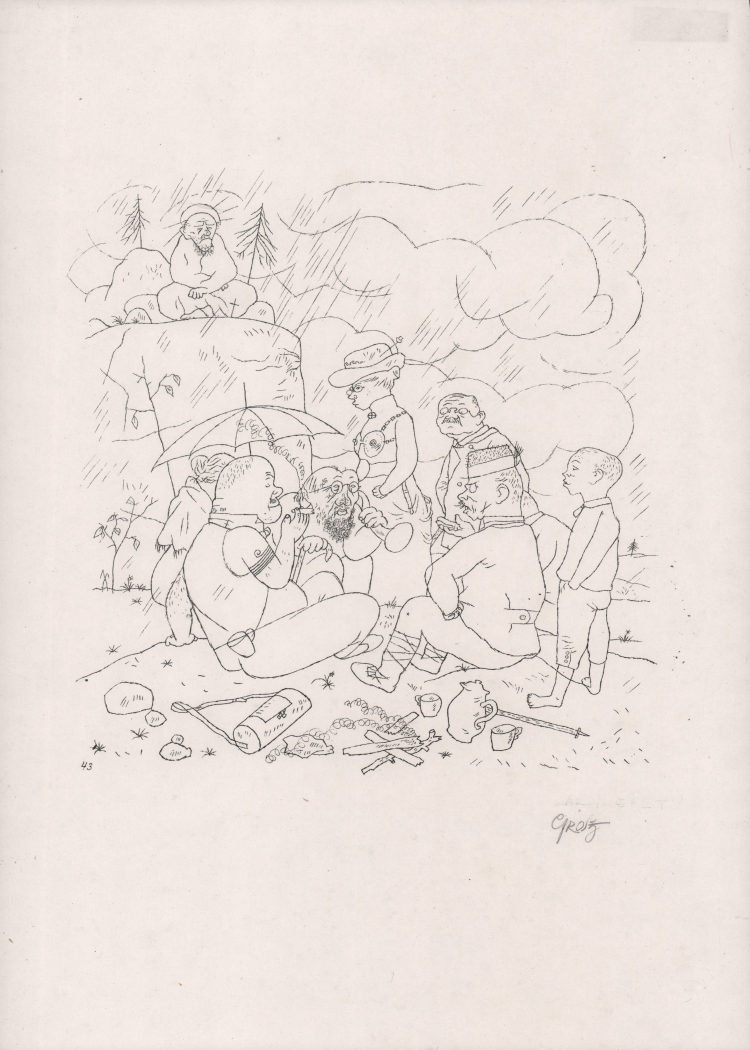

Original lithograph by George Grosz, plate 43 from Ecce Homo. From an edition of 40, signed in pencil by George Grosz. At lower right.

A fine impression, printed on contemporary wove paper, some foxing, otherwise very good condition.

“Ecce Homo”, published by the Malik Verlag in five different editions during the weeks of the turn of year 1922/1923, is a selected compendium of drawings by Grosz from 1915 to 1922: critical of their time and society, biting and satirical. The large total edition of the watercolours and drawings (10 000 copies) replicated in a meticulous reproduction process was meant to guarantee their mass distribution. As Alexander Dückers emphasises, George Grosz's drawn work is hardly to be divided from his printed work, and it is downright characteristic that, after 1918, in keeping with his “undogmatic” concept, the artist published “almost exclusively photolithographs and offset prints after drawings, that is, graphic reproductions” (A. Dückers).

The artist and the publishers Julian Gumperz and Wieland Herzfelde were put on trial in 1923/1924 because “Ecce Homo” contained numerous sheets that offended “the sense of shame and decency of a person with normal perceptions in regard to sexuality” - as stated in the charges. “However, the court did not consent to the prosecution's claim that the entire 'Ecce Homo' portfolio be confiscated and destroyed. It determined only that 17 of the 84 drawings and five of the 16 reproductions of watercolours were to be removed from the work.”

George Grosz, stage name of Georg Ehrenfried Groß (Berlin, July 26, 1893 - Berlin, July 6, 1959), was a German painter. Between 1909 and 1911 he studied at the Academy of Dresden, with the intention of fully understanding the techniques of representation of classical authors. He made copies of works by the old masters, especially Rubens, exhibited in the Dresden picture gallery, in this period also performed drawings for newspapers and satirical magazines, using the tool of caricature. In 1913 he stayed in Paris, where he came into contact with the avant-garde of Cubism and Futurism and where he could admire the works of Francisco Goya, Honoré Daumier and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. It was in these years that his style underwent a process of progressive simplification of forms, under the influence of expressionism, cubism and futurism, widespread among the young artists of the time.

Literature

A. Dückers, George Grosz, das druckgraphische Werk p.72-85; Wieland Herzfelde (introduction), Der Malik-Verlag, 1916-1947, exhib. cat. Deutsche Akademie der Künste Berlin, Berlin (Ost) 1966, cat. no. 59; Lothar Lang, George-Grosz-Bibliographie, in: Marginalien, Zeitschrfit für Buchkunst und Bibliophilie, 30th issue, July 1968, p. 1 ff, no. 38; Rosamunde Neugebauer, Georges Grosz, Macht und Ohnmacht satirischer Kunst. Die Graphikfolgen "Gott mit uns", Ecce Homo und Hintergrund, Berlin 1993, p. 81 ff.

Georg GROSZ (Berlino 1893 - 1959)

|

George Grosz, stage name of Georg Ehrenfried Groß (Berlin, July 26, 1893 - Berlin, July 6, 1959), was a German painter. Between 1909 and 1911 he studied at the Academy of Dresden, with the intention of fully understanding the techniques of representation of classical authors. He made copies of works by the old masters, especially Rubens, exhibited in the Dresden picture gallery, in this period also performed drawings for newspapers and satirical magazines, using the tool of caricature. In 1913 he stayed in Paris, where he came into contact with the avant-garde of Cubism and Futurism and where he could admire the works of Francisco Goya, Honoré Daumier and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. It was in these years that his style underwent a process of progressive simplification of forms, under the influence of expressionism, cubism and futurism, widespread among the young artists of the time. In 1914 Grosz enlisted in the German army, but was soon discharged for health reasons, but it seems that the real reason for the discharge was a psychological shock for which he was hospitalized in a military hospital. Returning to painting, between 1915 and 1917 the graphic reduction of the sign was radicalized to express the moral collapse following the defeat of Prussia: on this style Grosz based the production of the following years, characterized by adhesion to the Berlin Dada movement and revolutionary political positions. To the events that are located between 1917 and 1918 refers "The funeral. Dedicated to Oskar Panizza", an emblematic painting in which the author represents the allegory of humanity gone mad, prey to corruption and evil. It is a grotesque vision, desecrating and macabre tones where the same buildings that appear on the scene seem about to collapse and overwhelm the crowd. Of particular effect is the coffin placed in the center of the composition where a white skeleton is sitting. Another figure that stands out is the priest who, with his arms raised, holds in his right hand a white crucifix that has the function of placating the three monstrous and deformed beings that parade in front of him and that represent alcoholism, syphilis and the plague. The painting is dedicated to Oskar Panizza who, at the end of his medical studies and after having published poems irreverent towards the regime, was tried and imprisoned and then interned in some psychiatric hospitals and finally died in 1921. The work, pervaded by a highly ironic and pessimistic vein by the author, is an attack on the bourgeois society unable, according to Grosz, to prevent the tragedy of the First World War. In 1919 he was arrested for having participated in the Spartacist revolt; in the same year he joined the Communist Party of Germany. Since 1920 he was repeatedly denounced and tried for incitement to class hatred, contempt, contempt of religion and insults against the armed forces. The artistic production of those years was based on a language of cubist and futurist matrix that started from artistic sources of the past to arrive at popular iconographic models. So he passed from caricature drawings to apocalyptic and violent urban views to a programmatically political graphics, and finally to the New Objectivity movement, in whose Mannheim exhibition of 1925 Grosz participated. In the paintings, but above all in the drawings and lithographs of this period, the immense tragedy of post-war Germany is reflected. Streets, hovels, living rooms, barracks, are as vivisected by the corrosive pencil of Grosz, who without irony mercilessly reveals the hypocrisy and violence. His harsh and angular style, sometimes childish and violently explicit, is ideal for illustrating wretched people, prostitutes, drunks, murderers, wounded soldiers, with a violent component of social criticism against the ruthless greed of the ruling classes and vulgar businessmen, hidden under the mask of respectability. The deformations of expressionism and the simplifications of childish drawing and popular imagination give a raw incisiveness to the sign, while the multiple planes and simultaneous effects of cubism and futurism give analysis and precision to the details, in an exalted and visionary overall structure. His drawings, many of them in ink and watercolor, have contributed greatly to the image that many have of Germany in the twenties. In 1933, with the advent of Nazism, George Grosz was considered a degenerate artist and for this reason he left Germany to teach in New York; in 1938 he obtained the citizenship of the United States. The production of the American period is however less incisive, despite the returns, in surrealist key, to the violent and ruthless graphics of the past. In 1958 he returned to live in Germany. George Grosz died in Berlin on July 6, 1959 at the age of 65. The cause of his death is very peculiar: arrived late at night in front of his house, very drunk, opened the door of the cellar instead of the entrance. The result was a disastrous fall that cost him his life. He invented, together with John Heartfield, the technique of photomontage.

|

Georg GROSZ (Berlino 1893 - 1959)

|

George Grosz, stage name of Georg Ehrenfried Groß (Berlin, July 26, 1893 - Berlin, July 6, 1959), was a German painter. Between 1909 and 1911 he studied at the Academy of Dresden, with the intention of fully understanding the techniques of representation of classical authors. He made copies of works by the old masters, especially Rubens, exhibited in the Dresden picture gallery, in this period also performed drawings for newspapers and satirical magazines, using the tool of caricature. In 1913 he stayed in Paris, where he came into contact with the avant-garde of Cubism and Futurism and where he could admire the works of Francisco Goya, Honoré Daumier and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. It was in these years that his style underwent a process of progressive simplification of forms, under the influence of expressionism, cubism and futurism, widespread among the young artists of the time. In 1914 Grosz enlisted in the German army, but was soon discharged for health reasons, but it seems that the real reason for the discharge was a psychological shock for which he was hospitalized in a military hospital. Returning to painting, between 1915 and 1917 the graphic reduction of the sign was radicalized to express the moral collapse following the defeat of Prussia: on this style Grosz based the production of the following years, characterized by adhesion to the Berlin Dada movement and revolutionary political positions. To the events that are located between 1917 and 1918 refers "The funeral. Dedicated to Oskar Panizza", an emblematic painting in which the author represents the allegory of humanity gone mad, prey to corruption and evil. It is a grotesque vision, desecrating and macabre tones where the same buildings that appear on the scene seem about to collapse and overwhelm the crowd. Of particular effect is the coffin placed in the center of the composition where a white skeleton is sitting. Another figure that stands out is the priest who, with his arms raised, holds in his right hand a white crucifix that has the function of placating the three monstrous and deformed beings that parade in front of him and that represent alcoholism, syphilis and the plague. The painting is dedicated to Oskar Panizza who, at the end of his medical studies and after having published poems irreverent towards the regime, was tried and imprisoned and then interned in some psychiatric hospitals and finally died in 1921. The work, pervaded by a highly ironic and pessimistic vein by the author, is an attack on the bourgeois society unable, according to Grosz, to prevent the tragedy of the First World War. In 1919 he was arrested for having participated in the Spartacist revolt; in the same year he joined the Communist Party of Germany. Since 1920 he was repeatedly denounced and tried for incitement to class hatred, contempt, contempt of religion and insults against the armed forces. The artistic production of those years was based on a language of cubist and futurist matrix that started from artistic sources of the past to arrive at popular iconographic models. So he passed from caricature drawings to apocalyptic and violent urban views to a programmatically political graphics, and finally to the New Objectivity movement, in whose Mannheim exhibition of 1925 Grosz participated. In the paintings, but above all in the drawings and lithographs of this period, the immense tragedy of post-war Germany is reflected. Streets, hovels, living rooms, barracks, are as vivisected by the corrosive pencil of Grosz, who without irony mercilessly reveals the hypocrisy and violence. His harsh and angular style, sometimes childish and violently explicit, is ideal for illustrating wretched people, prostitutes, drunks, murderers, wounded soldiers, with a violent component of social criticism against the ruthless greed of the ruling classes and vulgar businessmen, hidden under the mask of respectability. The deformations of expressionism and the simplifications of childish drawing and popular imagination give a raw incisiveness to the sign, while the multiple planes and simultaneous effects of cubism and futurism give analysis and precision to the details, in an exalted and visionary overall structure. His drawings, many of them in ink and watercolor, have contributed greatly to the image that many have of Germany in the twenties. In 1933, with the advent of Nazism, George Grosz was considered a degenerate artist and for this reason he left Germany to teach in New York; in 1938 he obtained the citizenship of the United States. The production of the American period is however less incisive, despite the returns, in surrealist key, to the violent and ruthless graphics of the past. In 1958 he returned to live in Germany. George Grosz died in Berlin on July 6, 1959 at the age of 65. The cause of his death is very peculiar: arrived late at night in front of his house, very drunk, opened the door of the cellar instead of the entrance. The result was a disastrous fall that cost him his life. He invented, together with John Heartfield, the technique of photomontage.

|