| Reference: | S46681 |

| Author | Hieronimus HOPFER |

| Year: | 1550 ca. |

| Measures: | 218 x 242 mm |

| Reference: | S46681 |

| Author | Hieronimus HOPFER |

| Year: | 1550 ca. |

| Measures: | 218 x 242 mm |

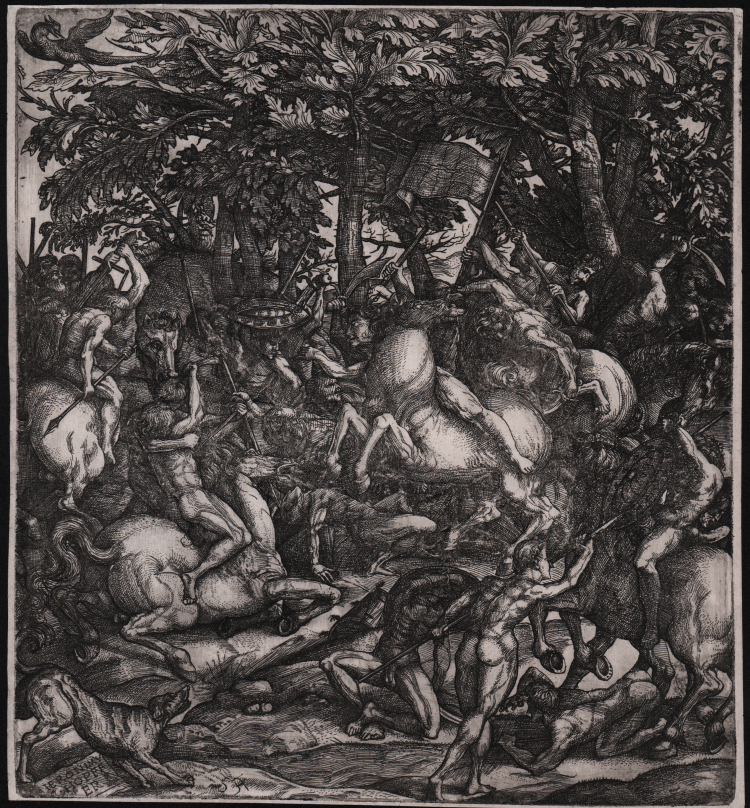

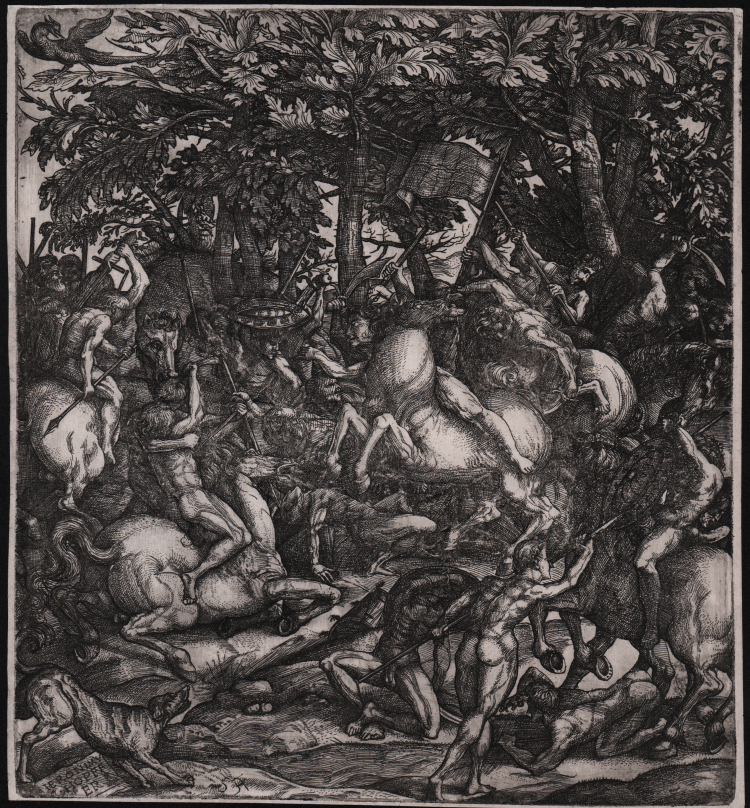

Battle of naked men; copy after Domenico Campagnola (Hind 4); combat between horsemen and foot soldiers in a forest.

Etching on iron, circa 1550, signed in the plate at lower left: 'IERONIMU/S HOPFF/ER' (followed by Hopfer's device).

A fairly close etched copy of Campagnola's Battle of Nude Men. The major changes occur in the leaves, which are larger, fleshier, more numerous, and more prominent than in the original; a large bird perched on one of these leaves is added at the upper left.

“The Battle of Nude Men is one of Domenico's two largest engravings, and the composition is surely the most complicated and ambitious of the whole group; in the handling of the nudes, the treatment of the landscape, and the frenetic actions of the figures, it is also among his most characteristic designs. Though Domenico is unlikely to have intended a specific encounter, he brilliantly evoked the tumult and confusion of a battle all'antica, much as his Milanese contemporary, the Master of 1515, did in his Battle. Both central Italian and Venetian sources for Campagnola's print have been suggested. Hind and the Tietzes believed that the ultimate model would have been Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari, a work never completed but elaborately prepared in drawings and, undoubtedly, cartoons. Leonardo's design was so celebrated in the early sixteenth century that numerous artists made variations on it, some of which could have been available to Domenico, as Oberhuber has recently argued. According to Suida, however, the engraving reflects the ideas of Titian, who was com missioned to paint a large battle picture for the Doge's Palace in 1513; although Titian did not execute the painting until 1537 (it was subsequently destroyed in a fire of 1577), he did work on preliminary designs until 1516. That Domenico's Battle of Nude Men was indebted to Titian's early plans for this commission is generally discounted for a variety of reasons. Yet we know from a document of 1514 that Titian had prepared modelli for his picture, and although none of these has survived, there is no reason why Domenico, whose closeness to Titian is universally admitted, might not have had access to them or to other studies that no longer exist. It has been objected that Titian would have designed a battle in contemporary costume and in a specific locale, rather than a skirmish of generalized nudes in a wood. But Domenico may have departed from Titian in just those features, and moreover Titian's own drawing for the composition he finally completed in 1537 appears to be populated, for the most part, with nudes. Although the theory that Leonardo was, indirectly, Domenico's source of inspiration need not be discarded, the direct influence of Titian seems more plausible to the present writer. Of course Titian was himself undoubtedly influenced by Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari. Titian's woodcut of c. 1514-15, The Submersion of Pharaoh's Army in the Red Sea should also be compared to Campagnola's battle scene; and a drawing in Chicago of a Battle Scene with Horses and Men, by Domenico himself, is very similar to the engraving though not directly related to it” (cfr. Mark J. Zucker Early Italian Masters in “The Illustrated Bartsch” vol. 25 (Commentary), pp. 510-511, n. 013).

“The recent rediscovery of Pisanello's wall paintings in the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua has proved in a spectacular manner how important battle and tournament scenes were in the Renaissance for the decorative programs of princely palaces and public buildings. Battle scenes demanded from the artist great skill in the arrangement of the composition and full mastery of the representation of men and horses in motion. It is not surprising that engravers repeatedly took up the subject: Pollaiuolo produced the Battle of the Nudes, Francesco Rosselli a David and Goliath (H. 1, Β.11.6), and the Master of 1515 a fierce Battle in a Wood (H. 17). The most famous battle pieces of the early sixteenth century were Michelangelo's Battle of Cascina and Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari, both designed for the Sala dei Cinquecento of the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence. Neither was ever finished, but the cartoons and preparatory drawings exercised a tremendous influence on many artists. After seeing them, both Raphael and his contemporary, Girolamo Genga, executed a great number of drawings of nude figures fighting, elaborating Leonardo's ideas and incorporating other motifs drawn from antique sarcophagi. It is likely that Campagnola had seen such drawings. In 1513, Titian had offered to paint a battle scene for the Palazzo Ducale in Venice; he began it only in 1537, however, and finished it the following year. The picture, his famous Battle of Cadore, was destroyed in the fire of 1577. Titian without a doubt had begun to think about the composition by the time of Domenico's engraving, and it has been suggested that the print may reflect some of these early ideas. This cannot be proved, as all of the extant drawings for the composition by Titian are surely from the period of the picture's execution. Yet Titian's magnificent woodcut of the Drowning of Pharaoh's Army in the Red Sea, executed around 1514, does give us some idea of what a battle scene from that early period would have looked like. It is thus clear that Domenico learned much from Titian in the spatial arrangement of the composition and the use of sweeping diagonals. The barking dog in the left foreground functions as a repoussoir much like the figure of Moses in Titian's print. Domenico does not, however, strive for Titian's clarity in the rendering of space, nor does he attempt to unify the composition in the same grand manner. Moreover, the men and horses in Titian's print are more powerful and massive and yet at the same time move with greater lightness and unity of body and limbs. Domenico's achievement was quite different. Using classical compositional formulas and deforming the shapes of the men and horses to increase the sense of movement and excitement, he created a haunting scene of confusion and turmoil; the individual figures and episodes are submerged in the general darkness, while the flickering light here and there picks out an arm, a face, a thigh, a muscular back, or the anguished form of a fallen horse. A drawing by Domenico Campagnola in the Art Institute of Chicago deals with the same subject” (cfr. Konrad Oberhuber in “Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art”, pp. 428-429, n. 156).

Hieronymus Hopfer (Augsburg, c. 1500 - Nuremberg, 1563) was born around 1500 as the second son of Daniel Hopfer. Only few biographical data are known: in 1529 the Augsburg City Council allowed him to go to Nuremberg for a year while, in 1531, Hopfer completely renounced his traditional civil rights and after 1550 he died in Nuremberg. Most of the known works are copies based on woodcuts and engravings by German (Dürer, Cranach) and Italian (Barberi, Campagnola, Mantegna) artists, as well as engravings based on medals and reliefs. Unlike Dürer and the other Nuremberg masters of engraving, Hieronimus Hopfer used to make his works in etching and on iron plate rather than copperplate, a technique in which he was a specialist along with the other members of the engraving family, his father Daniel and brother Lambert Hopfer.

The new technique in printmaking (although long used to decorate metalwork), etching involved biting lines into an iron plate with acid rather than scraping them with a burin. The earliest surviving print in the technique - by Urs Graf - dates from 1513. Dürer’s brief experimentation with this form of printmaking, between 1515 and 1518, does not appear to have proved particularly satisfying to him, and he soon concentrated on engraving, his preferred method of incising a plate.

Magnificent proof, printed with tone on contemporary thin paper, with margins, in good condition. Example in the second state of two, with the added number “591” at the lower edge.

Bibliografia

Hollstein, German engravings, etchings and woodcuts c.1400-1700, n. 49.II; Bartsch, Le Peintre graveur (VIII.518.44); cfr. Jay A. Levinson, Konrad Oberhuber, and Jacquelyn Sheehan, Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1973, n. 156; Mark J. Zucker Early Italian Masters in “The Illustrated Bartsch” vol. 25 (Commentary), pp. 510-511, n. 013; Hind, Early Italian Engraving, a critical catalogue n. 4.

Hieronimus HOPFER (Augsburg 1500 circa - Norimberga 1563)

|

The Hopfers were a German family of engravers. In 1497 Daniel Hopfer married Justina Grimm, sister of the publisher and humanist Sigismund Grimm. From the marriage were born sons Hieronymus and Lambert, who followed their father's profession and worked with him. Daniel made more than 130 prints of various subjects for the market of the time, Hieronymus 77 and Lambert 34. They placed their initials within the design in almost all of their prints (D.H., I.H., L.H.), adding a small emblem, such as the pine cone in the Augsburg city coat of arms, or a hop flower, in reference to the family name. Hieronymus Hopfer (Augsburg, c. 1500 - Nuremberg, 1563) was born around 1500. Only few biographical data are known: in 1529 the Augsburg City Council allowed him to go to Nuremberg for a year while, in 1531, Hopfer completely renounced his traditional civil rights and after 1550 he died in Nuremberg. Most of the known works are copies based on woodcuts and engravings by German (Dürer, Cranach) and Italian (Barberi, Campagnola, Mantegna) artists, as well as engravings based on medals and reliefs. Unlike Dürer and the other Nuremberg masters of engraving, Hieronimus Hopfer used to make his works in etching and on iron plate rather than copperplate, a technique in which he was a specialist.

|

Hieronimus HOPFER (Augsburg 1500 circa - Norimberga 1563)

|

The Hopfers were a German family of engravers. In 1497 Daniel Hopfer married Justina Grimm, sister of the publisher and humanist Sigismund Grimm. From the marriage were born sons Hieronymus and Lambert, who followed their father's profession and worked with him. Daniel made more than 130 prints of various subjects for the market of the time, Hieronymus 77 and Lambert 34. They placed their initials within the design in almost all of their prints (D.H., I.H., L.H.), adding a small emblem, such as the pine cone in the Augsburg city coat of arms, or a hop flower, in reference to the family name. Hieronymus Hopfer (Augsburg, c. 1500 - Nuremberg, 1563) was born around 1500. Only few biographical data are known: in 1529 the Augsburg City Council allowed him to go to Nuremberg for a year while, in 1531, Hopfer completely renounced his traditional civil rights and after 1550 he died in Nuremberg. Most of the known works are copies based on woodcuts and engravings by German (Dürer, Cranach) and Italian (Barberi, Campagnola, Mantegna) artists, as well as engravings based on medals and reliefs. Unlike Dürer and the other Nuremberg masters of engraving, Hieronimus Hopfer used to make his works in etching and on iron plate rather than copperplate, a technique in which he was a specialist.

|