| Reference: | S39487 |

| Author | Thomas de LEU |

| Year: | 1601 |

| Measures: | - x - mm |

| Reference: | S39487 |

| Author | Thomas de LEU |

| Year: | 1601 |

| Measures: | - x - mm |

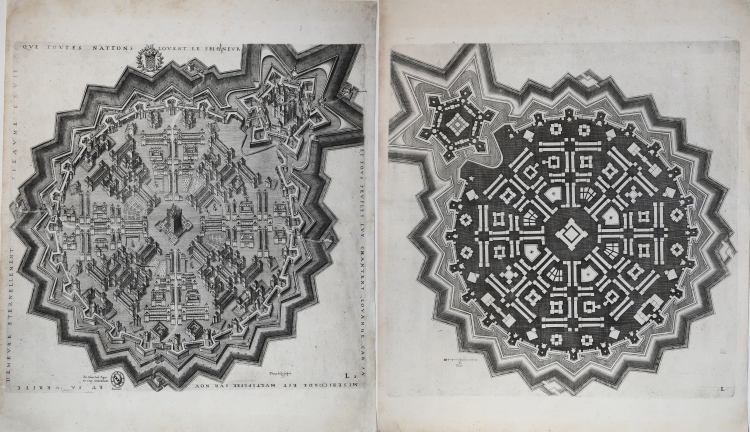

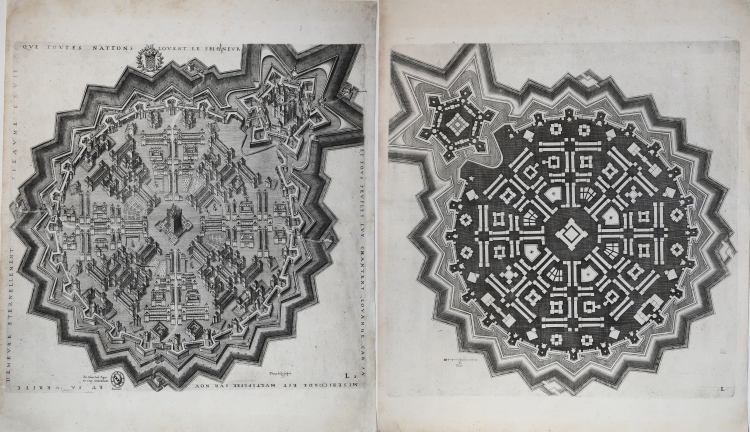

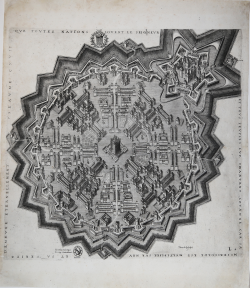

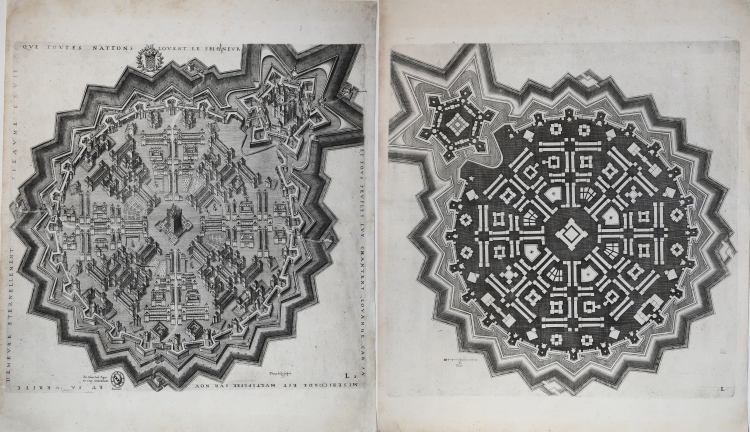

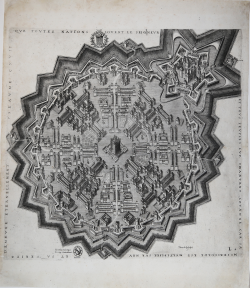

Etching, numbered at bottom right "L", scale at bottom left, graphic scale expressed in Toises. Imprinted on contemporary watermarked paper, large margins, in excellent condition. Sheet dimensions: 402 x 407.

Planimetry of the Huguenot Citadel shown in the second plate.

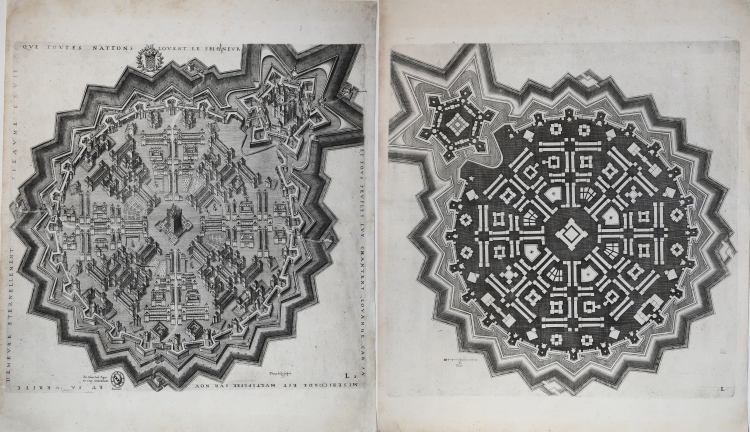

Etching, numbered "L2" on the bottom right, next to the signature "Thomas de Leu Sculpsit". On the left "En Dieu Seul Repos/ Et Vray contentement" with Perret's excudit next to it. Printed on contemporary laid paper, large margins, in excellent condition.

Encircling the fortress—a regular polygonal city defended by twenty-three bastions, crowned with a pentagonal citadel, and replete with religious, civic, and domestic structures—is a Psalm which encapsulates a Calvinist conception of society, sound and space.

“QVE TOVTES NATIONS LOVENT LE SEIGNEVR ET TOVS PEVPLES LVY CHANTENT LOVANGE CAR SA MISERICORDE EST MVLTIPLEE SVR NOV ET SA VERITE DEMEVRE ETERNELLEMENT PSEAVME CXVII”

The inclusion of this Psalm 117 into the Genevan Catechism’s 1545 Action de graces aprės le repas would have burned these two lines into the consciousness of French-speaking Protestants. Its regular phenomenological iteration as ritual song before the communal breaking of bread committed the Psalm to individual and social memory through melody, language, public performance, and its relation to bodily sustenance. On a broader scale, the Psalm meshed with a theological conception of geographical conquest. In his commentary on the verses, John Calvin exhorts readers to take seriously the words that “toutes nations” will resound in praises to the true God: while not all Gentiles would become believers, those who did would “be spread over the whole world.” By their daily chanting or reading these verses, the Huguenots would enter into literal harmony with a physically expansive community of believers, as well as with the natural landscape itself.

Given this theological framework, it’s interesting to note the relation—or lack thereof—between Perret’s structures and their surrounding contexts. Successful fortification treatises, such as the much-consulted works of Francesco de’ Marchi and Jean Errard, were not merely theoretical exercises: their idealized geometric principles had to be adaptable to the specificities of real sites. But Perret explicitly distinguishes his own work from these treatises: “Pour ce que plusiers ont écrit des principes de géométrie, fortifications, architecture et perspective, je n’en met point en ce livre.” Despite their formal similarities with Perret’s structures, Errard’s fortresses are emphatically planted in real physical space.

Perret’s fortified cities instead appear to float on the paper’s surface, describing an alternative religious “geography.” They recall Calvin’s Neoplatonic commentary on Psalm 117, which describes a nature that, despite its insentience, seems to speak. For if “rational creatures” sing verbal praises, the “Holy Spirit elsewhere calls upon the mountains, rivers, trees, rain, winds, and thunder, to resound the praises of God, because all creation silently proclaims him to be its Maker.” For modern readers, the highly regularized “ideal” cities of the Fortifications may appear to be technical drawings, albeit of high aesthetic value, but for Huguenot readers of the time, these structures—coupled with the surrounding sacred inscriptions—would have conveyed an entirely different emotive meaning. Calvin deliberately rejected dry academicism, placing music at the heart of his theology for its power in aiding the subjective internalization of the Word.

Published three years after the 1598 proclamation of the Edict of Nantes, the Huguenot architect’s treatise reveals a tight bond between notions of sound and territoriality during the French Wars of Religion. Inscriptions on Fortifications’ illustrated plates borrow scriptural verses co-translated into French by poet Clément Marot and theologian Theodore Beza for Calvinist Psalters. These were among the most widely circulated printed books of the French Renaissance, and Huguenots wielded them toward militant ends: Psalms were sung to steel Protestant soldiers marching into battle, to disrupt Catholic services, and to rouse anti-clerical sentiment during mass demonstrations.

Considered within this context, the treatise’s understudied inscriptions open new interpretive avenues into Perret’s designs. Against a Catholic conception of sacred geography, Perret’s radially-planned ideal cities function as open commercial and transportation infrastructure. Urban space is perfectly choreographed for the easy movement of Protestant worshippers, whose songs could spread unimpeded through the all the cities’ streets. There is also a unity of conception between Perret’s famous "perspectives" and his invocation of the aural experience of his cities. Cut-away axonometric representations of Protestant temples invite faithful readers to enter and fill the structures with a living, breathing, and worshiping body of saints. (The Textual-Sonic Landscapes of Jacques Perret’s Des Fortifications et Artifices by Morgan NG.)

Jacques Perret was architect and engineer to Henri IV. He also produced books on the arts of architecture, perspective and fortification.

|

Dusmenil, X, n. 96.

|

Thomas de LEU (c. 1555 - c. 1612)

|

French engraver, publisher and print dealer. The son of a dealer in Audenarde, he worked first at Antwerp for Jean Ditmar (c. 1538–1603) and then went to Paris before 1580 to work for the painter and engraver Jean Rabel (1540/50–1603). He married first Marie, daughter of Antoine Caron, in 1583, and secondly, in 1605, Charlotte Bothereau. He skilfully moved from the side of the militant Catholic League in the Wars of Religion to that of Henry IV, and as a result made himself a fortune. He ran a busy workshop and published large numbers of prints by other hands. Among his apprentices were Jacques Honnervogt (fl 1608–35) and Melchior Tavernier (c. 1564–1641). His first dated engraving is Justice (1579; Linzeler, no. 57), after Federico Zuccaro (1540/42–1609). He specialized mainly in portraiture (more than 300 plates), for example Catherine de ’ Medici (l 255), and in devotional engravings, such as Christ in Blessing (1598; l 7); he also made book illustrations.

|

|

Dusmenil, X, n. 96.

|

Thomas de LEU (c. 1555 - c. 1612)

|

French engraver, publisher and print dealer. The son of a dealer in Audenarde, he worked first at Antwerp for Jean Ditmar (c. 1538–1603) and then went to Paris before 1580 to work for the painter and engraver Jean Rabel (1540/50–1603). He married first Marie, daughter of Antoine Caron, in 1583, and secondly, in 1605, Charlotte Bothereau. He skilfully moved from the side of the militant Catholic League in the Wars of Religion to that of Henry IV, and as a result made himself a fortune. He ran a busy workshop and published large numbers of prints by other hands. Among his apprentices were Jacques Honnervogt (fl 1608–35) and Melchior Tavernier (c. 1564–1641). His first dated engraving is Justice (1579; Linzeler, no. 57), after Federico Zuccaro (1540/42–1609). He specialized mainly in portraiture (more than 300 plates), for example Catherine de ’ Medici (l 255), and in devotional engravings, such as Christ in Blessing (1598; l 7); he also made book illustrations.

|